SOUTH DAKOTA (South Dakota News Watch) – Sophie Stoffers carried groceries to her car in a Sioux Falls Hy-Vee parking lot and pondered a question from a reporter.

Would Initiated Measure 28, an effort on the Nov. 5 ballot to eliminate South Dakota’s sales tax on food, make life better for her?

“I’m always a fan of saving money,” said Stoffers, 24, who recently moved to Sioux Falls and works as an assistant athletic trainer at Augustana University. “But I don’t know much about (the measure). I need to hear the pros and cons before voting.”

According to U.S. Department of Agriculture data, an average family of four in South Dakota spends about $1,200 a month on food purchased at a store and prepared at home. Eliminating the 4.2% tax on food would save that household $50.40 a month, or about $600 a year.

Stoffers and her boyfriend have noticed grocery bills ticking upward. She’ll glance at the receipt on the way out of the store and try to cut back on nonessential items.

But that’s a long way from breaking down the ramifications of a sales tax cut on consumables, especially with differing viewpoints of what IM 28 will do.

Opponents pounced on the wording of the measure as broader than just groceries. They said it could cause a budget crunch by preventing the state from collecting sales tax on “consumable” items such as tobacco, toothpaste and toilet paper.

Estimates for the loss of state revenue range from $124 million to $646 million annually.

From a consumer perspective, national data shows that while the rate of inflation on food has softened, the price of grocery staples such as beef and eggs increased by 3.2% over the past year.

“This is the right thing to do,” said Rick Weiland, co-founder of Dakotans for Health, the petition-gathering group whose tax repeal effort was certified for the ballot with 22,315 signatures.

Assessing that statement means wading through a litany of factors, from legal language and tax policy to the ongoing conflict between a Republican-led Legislature and progressive groups that pursue policy change through citizen initiatives.

Here are the most pressing questions surrounding IM 28 as the November vote approaches.

What’s the argument for grocery tax repeal?

Supporters call the measure a long-overdue effort to take the tax burden off low-income families and individuals. South Dakota and Mississippi are the only states that fully tax food without offering credits or rebates.

The basic premise for eliminating the grocery tax is to make it easier for people to put food on the table within the constraints of their household budget.

“The tax is quite regressive,” Anna Phillips, an analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, told News Watch. “If you look at the percentage of household income spent on groceries, low-income earners spend roughly double the percentage of their income that high-income earners do on groceries. So this is going to make more of a meaningful difference to families who are currently struggling to get by.”

Feeding South Dakota, the state’s largest hunger relief organization, estimates that about 106,000 people in South Dakota, more than 11%, are food insecure, which means they lack reliable access to enough affordable, nutritious food. Of that number, 1 out of 6 are children.

Has this been tried before?

South Dakota’s grocery tax has been a target of legislative reform for decades, mostly by Democrats.

In 2004, the South Dakota Democratic Party gathered enough signatures to put a state food tax repeal on the ballot after legislative attempts to eliminate the tax fell short.

Opponents of the effort, including then-Gov. Mike Rounds, warned that passing the repeal would likely reduce the amount of state aid available for schools and health care.

Voters responded to that message and rejected the measure by a margin of 68% to 32%. Later attempts by state legislators to lower the tax on food or exempt groceries from the general sales tax rate also failed.

Weeks before being re-elected in November 2022, Republican Gov. Kristi Noem made a public pledge to preside over “the largest tax cut in state history,” a full repeal of the grocery tax. She vouched for its affordability and noted that voters might pass the repeal if lawmakers didn’t.

But legislators rejected Noem’s proposal during the 2023 session, opting instead to temporarily reduce the overall sales tax rate from 4.5% to 4.2%, with a sunset (or expiration) of 2027.

What’s the main argument against it?

There are fiscal consequences to eliminating the tax. Sales taxes are the largest source of state government revenue in South Dakota, one of seven states without a state income tax.

Phillips stressed that, while eliminating the grocery tax is a good way to advance racial and economic equity, states should pursue full repeals with caution due to budgetary impacts.

It’s important to remember that state revenue lost from eliminating the grocery tax would be on top of the $104 million estimated annual revenue loss from the overall sales tax cut passed by legislators in 2023.

So the question becomes: Can South Dakota afford to do this without having to cut important programs elsewhere or adding another tax?

Opponents of the measure answer that with a resounding no, citing what they said are ambiguous and problematic wording in the ballot measure.

The specific language of IM 28 prohibits the state from collecting sales tax on “anything sold for human consumption, except alcoholic beverages and prepared food.”

Nathan Sanderson, executive director of the South Dakota Retailers Association, said that wording is so vague that it could prevent the state from collecting sales tax on “consumable” items such as tobacco, toothpaste and toilet paper.

The Legislative Research Council took that a step further in a report to state legislators in July, extrapolating the “human consumption” definition to include propane and motor fuel and services rendered by a plumber or landscaper.

Weiland countered that it was the LRC and attorney general’s office that questioned earlier language in IM 28, which led to the current framework. He called for common sense, saying interpretations of the measure should be shaped by the stated intent of petitioners to target taxes on food and drink.

“You don’t drink gasoline,” Weiland said. “You don’t eat services.”

What kind of budget crunch are we talking about?

Well, it’s complicated.

Not even the LRC, which provides statutory and legal guidance for proposed ballot initiatives, has been consistent on what the impact will be.

Reed Hollweger, who resigned as LRC director during a meeting of the Legislature’s executive board in October 2023, addressed the potential for differing interpretations of “anything sold for human consumption” in a fiscal note sent to the secretary of state as required by law in January 2023.

“For purposes of this fiscal note,” he wrote, “the LRC assumes the phrase only includes food items because of the modifying language ‘except alcoholic beverages and prepared food’ and does not include personal tangible property and services, both of which can also be sold for human consumption. Other assumptions as to the meaning of this phrase may be just as reasonable, if not more so.”

With that qualification, the fiscal note said that the state could see a reduction in sales tax revenue of $123.9 million annually.

Sanderson estimated to News Watch in June that IM 28 would result in a budget downturn of at least $176 million annually because it would include tobacco products, defined in state law as “any item made of tobacco intended for human consumption.”

Then came the kitchen sink estimate the LRC presented to legislators as an update in July – a worst-case scenario analysis that said the budget impact could soar as high as $646 million annually.

So which number is right?

The official fiscal note produced by Hollweger uses the $123.9 million figure, while Attorney General Marty Jackley’s ballot statement noted that human consumption “is not defined by state law, but its common definition includes more than just food and drinks.”

Jackley’s statement also said that “judicial or legislative clarification of the measure will be necessary.” That’s the one thing that both sides agree upon.

Any judicial review will likely involve trying to find a “harmonious reading” of the conflicting statutes or language, according to Neil Fulton, dean of the University of South Dakota School of Law and former chief of staff to Rounds.

“The goal is to identify the intent of the enacting Legislature, or the people in this instance,” Fulton told News Watch. “Commonly, that’s found from the text alone because it’s free of ambiguity. But if the context or other aspects of the enactment lead to a different reading, or when a statute can be read multiple ways, the guiding star is, ‘What did the people intend?’”

How much of a problem is IM 28’s wording?

Phillips, the policy analyst, said the measure should have stipulated that the tax rate will be changed to 0% rather than saying the state “may not tax” consumables.

Eliminating the tax entirely would likely put South Dakota out of alignment with the Streamlined Sales Tax Project, a cooperative effort of states, local governments and the business community that standardizes collection of sales tax, she said.

“That agreement makes administration easier across states, both for vendors who have to comply with sales and use taxes as well as tax administrators,” said Phillips. “So removing the tax entirely on groceries will take South Dakota out of that agreement, which would be unfortunate.”

South Dakota could also lose revenue from the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, a 1998 pact among 46 states and major cigarette manufacturers as part of litigation for health care costs and deceptive trade practices.

Jackley has said that not taxing tobacco could jeopardize South Dakota’s share of that settlement, which amounts to about $20 million annually.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt poses with supporters on Feb. 27, 2024, in Oklahoma City after signing a bill to eliminate the state’s 4.5% sales tax on groceries. (Photo: Courtesy of Oklahoma Governor’s Office)

As for the “anything sold for human consumption” language, Phillips pointed to more specific wording used by Oklahoma legislators in a bipartisan effort to reduce the state’s tax on food and food ingredients to 0% earlier this year.

To stay aligned with the streamlined sales tax, the Oklahoma law defines food and food ingredients as “substances, whether in liquid, concentrated, solid, frozen, dried, or dehydrated form, that are sold for ingestion or chewing by humans and are consumed for their taste or nutritional value.”

That’s essentially the same standardized language found in South Dakota law, which Hollweger said in a letter to Dakotans for Health in 2022 would “likely apply” to the LRC’s original suggested language for the measure.

The Oklahoma law also states that the 0% tax rate does not apply to alcoholic beverages, dietary supplements, marijuana products, prepared food or tobacco.

Phillips said the differences between Oklahoma’s law and IM 28 underscore the difficulty of articulating complex tax policy through a ballot measure, which needs to be clear to voters and cannot encompass more than one subject under South Dakota law.

Fixing that language “shouldn’t be difficult to do,” she said. “I would imagine the Legislature would have a bit of an incentive to do it because they don’t want to blow that hole in their budget.”

What will legislators do if it passes?

Because IM 28 is an initiated measure, not a constitutional amendment, legislators have more power to craft the policy.

For instance, they can adjust the language to align with the definition found in South Dakota law, removing some of the unintended consequences cited by IM 28’s opponents.

“The counter to many of these complaints (about wording) is that the Legislature has eight months to fix it,” said Michael Card, an emeritus professor of political science at the University of South Dakota. “Part of this back-and-forth is due to efforts to limit the scope of initiated measures, a fight between the dominant (Republican) party and those who want to change laws through the ballot.”

Sanderson responded that even if the language is fixed and IM 28 is sharpened to include only groceries, there are still repercussions on top of the earlier general sales tax cut.

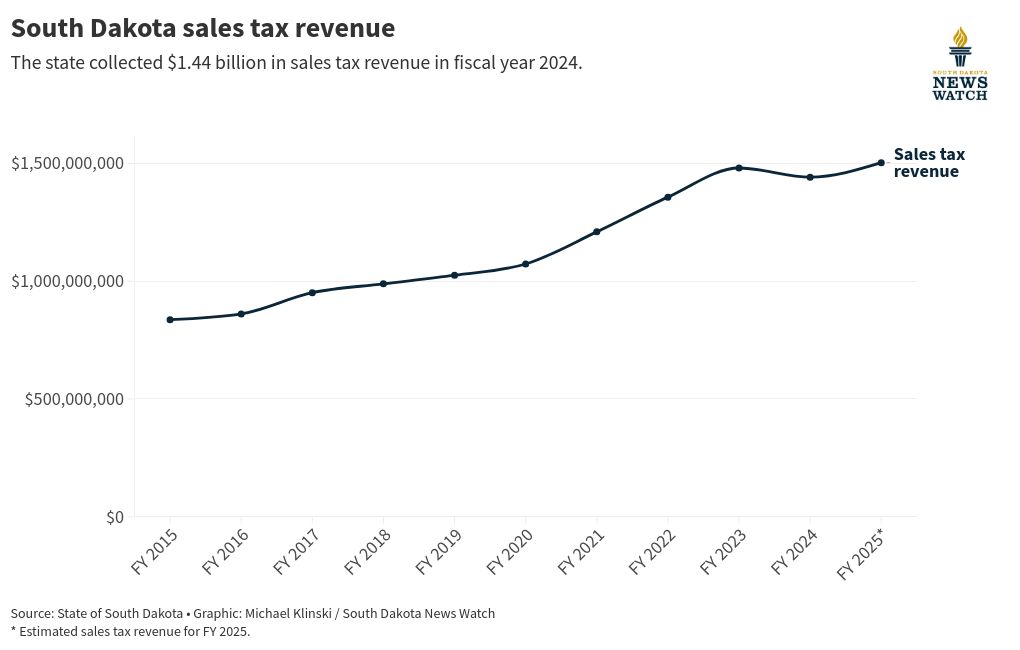

Sales tax receipts declined by 2.6% in fiscal year 2024 after gains of 9%, 12.2% and 12.7% the previous three years, according to the South Dakota Bureau of Finance and Management. That dip reflects the earlier sales tax cut and will require action if the state can’t tax groceries or other consumables, he said.

“The problem is that IM 28 doesn’t have any mechanism for replacing the lost revenue, so the money’s going to have to come from somewhere,” said Sanderson, who spearheads a coalition that opposes the measure.

“In order to make that up, they’re going to have to raise a tax somewhere. That requires a two-thirds vote of a Legislature in which 94 out of 105 are currently Republicans. Are legislators going to vote for a (sales) tax increase to raise revenue? I don’t think so. And that’s why we’ve expressed our concerns that if IM 28 passes, it’s going to lead to higher property taxes or an income tax (through ballot measure), because the Legislature is simply not going to vote with a two-thirds majority vote to raise the tax.”

Weiland called these claims scare tactics meant to influence voters and take the focus away from the merits of a grocery tax repeal.

He referenced past legislative overrides of resident-led initiatives such as IM 22, a campaign finance and ethics reform package approved by voters in 2016 that was later repealed by lawmakers with an emergency clause that ensured it could not be referred back to the ballot.

“I think every concern that’s been raised, if in fact it was a real concern and not a campaign tactic, they could address very simply in the upcoming legislative session,” said Weiland, a former Democratic candidate for U.S. House and Senate. “What I think they’re more likely to do is talk about this $646 million hole in their budget so they can declare a state of emergency and repeal it like they did with IM 22.”

Does Gov. Noem support a grocery tax repeal?

Noem personally testified in committee for her 2023 bill to repeal the grocery tax, based on her campaign pledge.

She pointed to double-digit increases in sales tax revenue in 2021 and 2022 and a budget surplus in 2022 of $115 million, an outlook boosted by COVID-related federal stimulus and inflation-impacted tax receipts.

The bill ultimately failed, but the message was duly noted by Dakotans for Health and other groups that have pushed for eliminating the grocery tax.

“The Republicans’ big argument has always been, ‘Oh, we don’t have the money to repeal the food tax. It will come on the backs of firefighters and teachers, or we’ll have to do a state income tax,’” Weiland said. “Well, the governor took all those arguments and threw them in the trash.”

But Jim Terwilliger, the governor’s budget director, noted that Noem’s proposal would have reduced the state’s food tax to 0% rather than eliminating it, addressing concerns about compliance with the streamlined sales tax agreement.

The bill’s language aligned with state definitions for food and food ingredients and it spelled out exceptions such as alcohol, tobacco and cannabis.

She warned lawmakers of potential budget fallout if voters passed a grocery tax initiative on top of the general sales tax cut, pointing to public support for such a measure.

Terwilliger told News Watch earlier this year that Noem doesn’t support IM 28 because of concerns about the wording. He added that the governor “still believes a repeal of the grocery tax is the best tax relief for South Dakota families if it is done in a responsible manner,” though she didn’t mention the repeal in her 2024 budget message or State of the State address.

Can cities and towns still tax groceries if this passes?

Again, it’s complicated. The actual wording of the measure states that “municipalities may continue to impose such taxes.”

But opponents, including the South Dakota Municipal League, said eliminating the tax, rather than reducing it to 0%, will render local governments unable to impose the food tax because of South Dakota Codified Law 10-52-2.

That law states that cities and towns can charge a sales tax if the tax “conforms in all respects to the state tax … with the exception of the rate.” Eliminating the tax entirely would create problems with state and local alignment, said Sanderson.

“Cities and towns can only tax the same items as the state,” he said. “So despite the language in IM 28, if the state cannot charge a tax on ‘anything for human consumption,’ neither can a municipality.”

Rapid City lawyer Jim Leach, who represents Dakotans for Health, called that a flawed analysis. His contention is that IM 28, if it passes, “becomes the law of

South Dakota” and supersedes the existing provisions, “which would allow municipalities to continue to tax food.”

Hollweger, in a written statement to News Watch before he resigned, noted that “only the state was specified” in Dakotans for Health’s final submission and that municipalities are not legally defined as agencies of the state. “Therefore, LRC concludes the proposed (ballot measure) would not prevent municipalities from imposing a sales tax on food,” he wrote.

Hollweger did not respond to an interview request for this story.

Fulton, the USD law school dean, pointed to a legal principle that says when there is a general statute and a more specific law on the same topic, the more specific statute wins out.

“In this instance, the court would be looking at how IM 28 fits, or doesn’t fit, with other taxation statutes and giving the right of way to the more specific statute,” he said.

What are the alternatives to grocery tax repeal?

Several states use refunded tax credits for low-income brackets in which consumers pay the full sales tax rate on food but recoup some of those added costs by claiming a credit when they file their taxes.

The benefit of this, Phillips said, is that the relief is targeted toward low-income households, which makes it more efficient. Simply cutting the grocery tax affects these low-income groups as well as higher-earning families that are likely not as reliant on state dollars that could be used for other services.

The downside, she added, is that “people are going to have to know to apply for it, especially if you are dealing with people on very low incomes or fixed incomes who may not even file income taxes.”

Even for those who do apply, the relief comes once a year during tax season, Phillips noted.

“If you’re a family that’s living paycheck to paycheck, you would rather take the benefits (every trip to the store) rather than waiting a year from now and getting it in a lump sum, which is harder to budget for,” she said.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit news organization. Read more in-depth stories at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email every few days to get stories as soon as they’re published. Contact investigative reporter Stu Whitney at [email protected].

Copyright 2024 KTIV. All rights reserved.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66f330039aa74ddebb96c1c5029cdba0&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ktiv.com%2F2024%2F09%2F24%2Fwhat-is-south-dakotas-food-tax-repeal-measure%2F&c=15426108099620563940&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-24 09:51:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.