For many, “mushroom” holds no value beyond the plate. Mushrooms are an additive on pizzas, an umami star of some Asian dishes like ramen, egg rolls, and stir-fries, cooked into omelets, and considered a triumphant delicacy of haut cuisine when finely grated over pasta. Others might hear “mushroom” and think of home ownership worries, like lawn care and tree health. The term “fungus” might be associated with mild disgust and thoughts of bathrooms and feet.

It would seem, then, that mushrooms and fungi get a bad rep – love them for food, but hate them for everything else. But these common ideas of fungi don’t tell the whole story, and some Rhode Islanders have found joy in the complexity, mystery, and strange beauty of the world of mycology – the study of fungi. They call themselves the Rhode Island Mycological Society (or RImyS, for short).

The society was established in 2022 by Deana Tempest Thomas, who holds “deep affection for fungi and a shared concern for their future.” The club was a way to create a link between scientific inquiry and public awareness about the Kingdom of Fungi, for despite fungi’s role in the ecosystem, “many Rhode Islanders remain unaware of their significance.”

Deana Tempest Thomas, president and founder of the society

Deana Tempest Thomas, president and founder of the society

Thomas had not always been involved in mycology. For most of her life, she took no notice of the mushrooms around her, even though she grew up in the woods of Scituate, where there is easy access to spot mushrooms. About five years ago, she stumbled across a purple mushroom, “and trying to ID that was like a puzzle,” Thomas remembers. “Then I found out they were connected to trees […] and that was it. I was hooked.”

The mushroom that got her into the world of fungi

The mushroom that got her into the world of fungi

Before she formed the society, Thomas was driving to Boston and various parts of Connecticut to be around other mushroom lovers and learn how to identify field and forage from other enthusiastic mycologists. “Learning about fungi has taught me to look more closely at this underground network [of mycelium],” she explains. The network she refers to is playfully called the “Woodwide Web.” Many fungal organisms interact with plants and trees through tiny threads called “mycelium” that actually bore into or wrap around the roots of another organism. All together, the mycelium creates a vast mycorrhizal network that connects individual plants together to communicate and transfer minerals, water, and other nutrients. This network is crucial for the health of the forest.

While the mycorrhizal network is usually symbiotic between fungus and tree, some species have evolved to act as a parasite to the Woodwide Web. Indian Pipe, or Ghost Plant, or scientifically named Monotropa uniflora does not photosynthesize. Instead, Thomas explains it taps into the mycorrhizal networks and steals a tree’s sugar. What happens in the underground can be just as exciting and complex as the ecosystems people can more readily see.

Fungi, as any member of the Rhode Island Mycological Society will tell you, are incredibly diverse. “Most fungi don’t make that picturesque thing we think of – the cap and stem,” describes Thomas, instead referencing the microscopic spores that are buried in the dirt, float on the water, or live on the bark of trees. Script lichen is a common example of the latter, called such because of the little black lines that run across a tree’s bark “which almost look like little hieroglyphs.” Some mushrooms are bioluminescent, meaning if you take them – fresh – into a very dark room, you might be able to see them gently glow. Others can be bulbous, vibrant in color, or as small as a fingernail. Some are truly bizarre: the Dog’s Nose Fungus is a wet, sticky black mushroom that resembles the cold, wet nose of a canine, while the Stinky Squid fungus is chthonic with its bright orange “tentacles” and odor that smells like rotting flesh.

“Stinky Squid” mushroom

“Stinky Squid” mushroom

The Stinky Squid falls under the mushroom description category of “phallic.” “In colonial times,” Thomas chronicles, “men would go around stomping them down to keep women’s eyes innocent.” Despite the abuse mushrooms suffer from being stomped, kicked, nibbled, or picked, actions asserted on the cap and stem don’t hurt the fungal specimen; mushrooms – the above ground, visible growth – are the fruit of the fungus, while the mycelium body is hidden, buried in the soil, or burrowed within a log or tree. The cap and stem are just a spore body, an encasing to hold the spores of the fungus until they are dispersed.

“We don’t really know the number of mushrooms that exist in Rhode Island” or that exist in the world, Thomas says. Scientists estimate there are at least 2.5 million species of fungi, but only around 160 thousand have been described. “In New England, including the [fungi] that don’t make mushrooms, there may be 20 thousand species, but we really don’t know.” That’s part of the mission of the society: to document the mushrooms club members find on sites like iNaturalist to further the scientific study. “Their whole way of living is so different from plants and animals. They weren’t elevated to Kingdom Fungi until 1969, which in terms of science isn’t that long ago. Before, we used to think of them as ‘lesser plants,’” Thomas explains.

This makes things difficult when trying to determine the species of mushroom on a walk. Not to mention that fungi are very climate- and temperature-dependent, so different mushrooms will appear in different areas, during different times of the year, and even look different depending on different conditions. For example, the white enoki mushrooms found in grocery stores are actually brown, thicker, and fuzzier when found in the wild; some fungi only grow during the winter season in cold weather, while others can only grow on well-rotted wood, old-growth trees, or in certain “epochs” of a forest, like when an area transitions from a meadow to woods. “Fungi can tell a story of time,” says Thomas.

There are some ways that can help mycologists (professionals or beginners) to identify mushrooms in the field. Species can be differentiated by color, bruising reactions along the stem and cap, gill patterns, texture (slimy, sticky, dry), scent (earthy, powdery, bleach, almonds, cherries, chlorine, etc.), and even taste (though it is best to spit it out after, just in case it is of the poisonous variety). Although she’s been studying mushrooms for years, Thomas still sometimes struggles with field identification, but promises that when “being mindful, slowing down, and looking for mushrooms, it’s amazing how one’s sense of awareness increases of living things around us. Humans have great pattern-recognition, so the more you practice looking, the more you see” and the easier and more readily fungal identification will come.

Thomas hopes that as more people become curious about fungi, more awareness will spread about their crucial role in the ecosystem and how little science actually knows about these organisms. In the midst of climate change and human interference with the underground ecosystem that has been overlooked for so long, Thomas worries that some fungus secrets will die out.

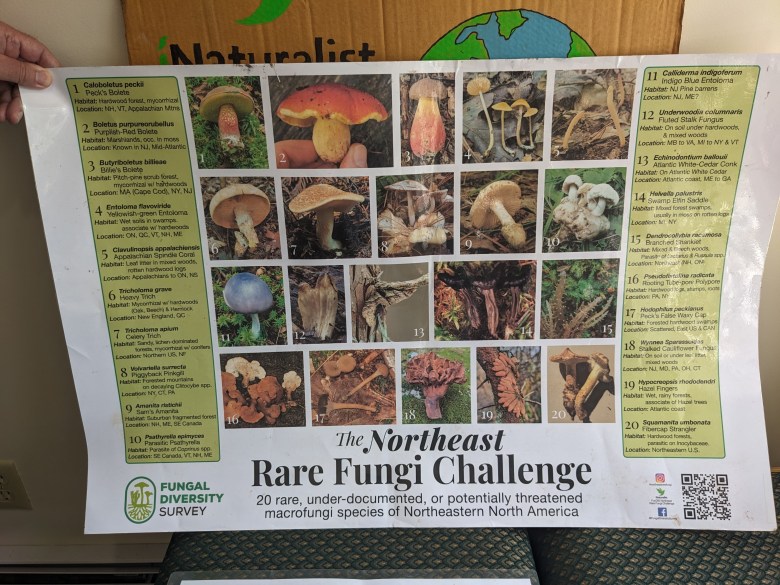

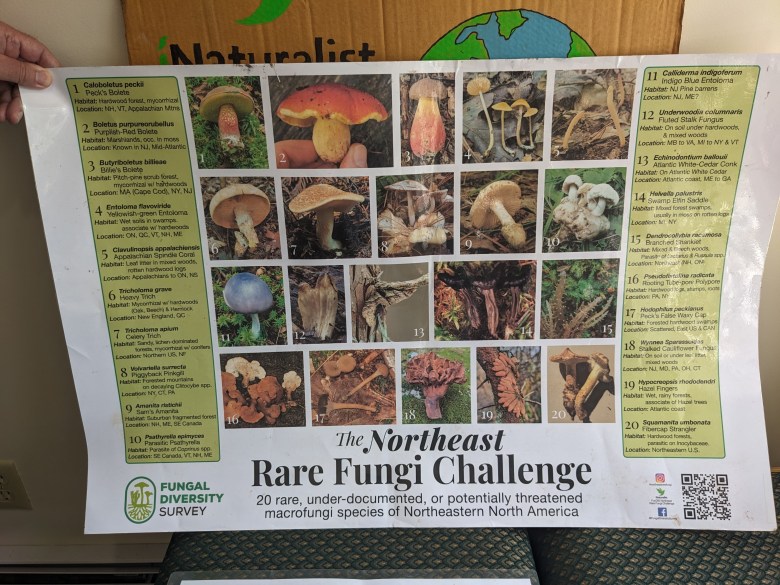

Non-native fungi, like golden oysters sold at markets, are “really aggressive rotters” that have escaped cultivation and are out-competing native varieties of fungi, and fungi were not introduced to the Red List – an international organization that lists species that are considered to be in danger of extinction – until the early 2000s. In 2013, two lichens and one fungus were put on the red list. Currently, only about 600 species are being assessed, and “over half of them we think are rare,” says Thomas. She encourages society members to participate in the Rare Fungi Challenge when they go on walks to help document and further scientific research and conservation efforts. “We need to look at fungi in a conservation way, and not a human way of ‘is this poisonous, can we eat it, or does it have medicinal properties.’” Anybody who finds an interesting mushroom – especially an uncommon or “rare” variety should take photos and share it on iNaturalist, with a land trust or park organization, or even on social media.

Since its inception, the Rhode Island Mycological Society has joined the North American Mycological Association (NAMA) and the Northeast Mycological Federation. Yearly membership is by household, and the society’s website and Facebook group advertise a variety of events, such as art, growing classes, walks, and field trip forays, “to bring mushrooms to everybody.”

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66eea42cc65f439eb1b3a2a4839647d2&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwhatsupnewp.com%2F2024%2F09%2Ffungus-among-us-an-underground-rhode-island-society-unites-the-mycologically-curious%2F&c=18187411878343499645&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-20 23:42:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.