A pear hangs in the mystery June’s Pear tree at Hawk Ridge Farm in Pownal. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

When art consultant June LaCombe moved into her 1848 farmhouse in Pownal almost 50 years ago, she was quickly captivated by the “magnificent” pear tree that dominated the back garden. It was “already an ancient tree” at the time, she said, and “very tall and beautiful.”

LaCombe enjoyed many seasons of juicy, succulent fruits, reaching the pears with apple ladders and picking poles, or harvesting drops that had fallen to the ground near the tree’s straight, slender trunk.

“All of the people on our road and all of our neighbors have collected pear recipes because we gave those pears to so many people,” she said.

At some point, LaCombe built an addition to her farmhouse at Hawk Ridge Farm and designed a stone wall to form a graceful comma around the tree’s base “as a celebration of that pear,” she said. “The whole back yard is a tribute to that pear tree.”

One year, Fedco Trees founder John Bunker, famed in Maine and beyond for identifying old and vanishing varieties of apples, came over to get a look at her beloved tree. He identified it as a Beurre d’Amanlis, an old, rare and fragrant French variety.

For years, that’s how things stood.

But was it really a Beurre d’Amanlis? Lauren Cormier, an ardent pear enthusiast, Bunker mentee and a Fedco Trees employee at the time, began to take a closer look at the fruit, and she had her doubts. She was reading old descriptions of old pear cultivars from old pear catalogues dating back to the 19th century, and when she compared the fruit from LaCombe’s tree with the Beurre d’Amanlis, “a few things were a little bit off,” she said.

For one, the stem was too fat. For another, the shape of the fruit seemed wrong. Also, its flesh was supposed to be greenish white, “but June’s pear doesn’t have that,” Cormier said.

Two years ago, Cormier, by then an orchard assistant at the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners’ Maine Heritage Orchard in Unity, got the chance to test her hunch. She sent a leaf from the tree to the USDA National Clonal Germplasm Repository in Corvallis, Oregon, for DNA testing.

When the results came back, her suspicion was confirmed. The tree was not a Beurre d’Amanlis, its DNA definitively proved. Nor did it match any other in the USDA pear repository, some 600 to 800 varieties at the time.

“It came back unique,” Cormier said, “a lost pear.”

She dubbed it “June’s Pear” for LaCombe, a provisional name, she said, until its identity can be discovered.

Maine has had a passionate coterie of apple “explorers” for several decades, Bunker foremost among them, who are intent on finding and preserving the state’s heirloom apple trees. Today, Maine’s heirloom pear trees – threatened by age, development, climate change and related pests and disease – are just beginning to get similar attention.

“There are a number of lost (Maine) pears,” Cormier said. “We have more digging through archives to do trying to find out the identity of these unique mystery pears. It is a pretty exciting time for pears!”

Lauren Cormier, Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners pear specialist and orchard assistant reaches for a pear she’s just picked from June’s Pear tree at Hawk Ridge Farm. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

PEARS WITH A PAST

Pears are not native to Maine. Like apples, they are thought to have been brought here, probably in the 17th century, with European settlers. For another hundred years or more, according to an article Cormier wrote for the 2022-23 winter issue of the Maine Organic Farmer & Gardener, they didn’t taste especially good.

The settlers used the pears to feed livestock and themselves, cooking and baking with them and preserving the fruit for long winters by canning and pickling, and fermenting them into perry (the pear equivalent of hard cider). These pears, never as numerous, popular or reliable in Maine as apples, were picked from seedlings, unique trees that grew from seed.

It wasn’t until around the 19th century that new European cultivars bred for deliciousness, the Beurre d’Amanlis among them, reached Maine, and that the practice of grafting took hold. Orchardists graft by joining a small branch from a desired tree, the scion wood, onto the trunk, or rootstock, of another tree to create a new tree that will bear genetically identical fruits to, clones of, the desired one.

Palermo resident Dan Newman, carpenter by day and pear (and apple) explorer by night, has studied these early cultivars, poring through records in old books, newspapers and pomological societies; and scrutinizing ribbon winners at local fairs and grange halls in order to rediscover and record the trees that historically grew in Maine.

He’s drawn up lists of European heirloom pears as well as about 15 lost “native Maine” pears, varieties that originated here as farmers planted seeds from promising European pears and attempted to adapt them to the local growing conditions. In the first part of the 20th century, as the U.S. fruit-growing industry specialized, shifted and consolidated, most of these pears fell out of favor and cultivation; today, at the Portland Farmers’ Market, it’s bartletts and boscs all day long.

But pear explorers feel certain the rare old cultivars, these Maine natives and wild seedling trees, too, still grow in Maine’s landscape: in backyards, as with June’s Pear; in the remnants of neglected orchards; and on farmland that is returning to forest.

And as Newman wrote in 2019 in his elegantly worded unpublished paper on “The Native Pears of Maine” about the now missing Fulton, Goodale and Eastern Belle varieties, “there is a strong probability that a dedicated effort to find them would be successful before they are lost forever.”

WHY BOTHER?

Newman and Cormier cite the unique flavors of these little-known fruits, the stories the trees can tell about Maine’s past, and the need – more urgent than ever as the climate changes – to preserve genetic diversity.

Commercial pears today are often bred for size, looks and their ability to travel. Old pears didn’t need to withstand cross-country or international treks to the supermarket; breeders could concentrate more on flavor. The old pomological records Newman quotes in his paper will make you long for a taste. The fulton pear had “Flesh half buttery, moderately juicy, with a sprightly, agreeable flavour.” The McLaughlin pear was “rich, sugary, slightly perfumed, and excellent,” while the Eastern Belle was “peculiarly rich and spicy.”

When these trees were mere saplings, Mainers were canning herring, making shoes, milling cotton, sailing clipper ships, building railroads, and lumbering.

“These are actually crops that were planted by a farmer generations ago,” Newman said. “These are literally where these trees were planted, put there by a person 150 years ago, and that is a really interesting piece of landscape history, of agricultural history, of local history.”

Looking forward, as the planet warms and pests and diseases spread, genetic diversity is ever more critical. Fire blight, for instance, which can kill pear (and apple) trees, is already more prevalent in Maine.

Suppose the anjou becomes susceptible to disease, the bartlett a victim to pests, the bosc at risk from increasingly hot summers? With luck, some of Maine’s heirloom and lost varieties may be more resistant and more resilient than the commonplace pears of today.

“We want to have more options, not less,” Cormier said.

Cormier also worries about the “club” problem. As a way to fund their research, apple breeders increasingly trademark and patent new varieties – think Jazz or Honeycrisp. Orchardists must then pay for licenses to grow these specialty apples. Cormier fears pears could be next.

“It is sort of the opposite of what we are doing at MOFGA,” she said. At MOFGA events such as the Common Ground Country Fair, which starts on Friday, the nonprofit sets out a big table of fruit tree scion wood and encourages farmers and gardeners to take some home “and graft these varieties so they don’t go extinct forever,” Cormier said.

MOFGA’s Laura Sieger removes the protective wrapping from the stem of an apple tree at the Maine Heritage Orchard in 2017, Michael G. Seamans/Staff photographer

GROWING AN ORCHARD

Ten years ago, in the face of such concerns, MOFGA created the 10-acre Maine Heritage Orchard in a reclaimed gravel pit, focused on cultivars that predate 1950.

The orchard is home to 300 types of apple trees (and about 350 trees), but just 18 pear trees so far, each thought to be different. Of that number, only five are old enough — seven to 10 years — to bear fruit. Pear trees mature slowly, hence “plant pears for your heirs,” an adage I heard several times while reporting this story, but they are long-lived. Some say they can live up to 350 years old. (Cormier guesses that June’s Pear at Hawk Ridge was planted in the late 1800s.)

Most of the pear varieties in the Unity orchard aren’t for sale (yet?) in nurseries in Maine, or anywhere else in the United States for that matter. Even their names are likely unfamiliar.

Several sound-like characters from old French novels: Doyenne Boussock, Louise Bon d’Avranches, Duchesse de Berry d’Ete. The less evocatively named kieffer was the perfect dooryard pear for pre-statehood Mainers, according to Cormier, because it was easy to grow, disease resistant and an abundant producer. It had just one serious drawback, she said: “If you bite into a kieffer, it’s almost inedible.”

This spring, the orchard got an exciting gift from the pear repository in Oregon: scion wood from 35 old dessert pear varieties, most of them known to have once grown in Maine. (A dessert pear is one that can be eaten out of hand as opposed to the more astringent perry pear varieties.)

Seth Yentes, of North Branch Farm in Monroe, grafted the scion wood and is nurturing the infant trees in the farm’s large nursery. Assuming they grow and thrive, they’ll be planted in the MOFGA orchard in 2026, tripling its heirloom pear tree count.

Yentes also grows many varieties of pear trees for Fedco.

“Pears have certainly been challenging,” he said, “a lot of trial and error to figure out how to grow them well.”

But it’s a challenge he relishes.

“Some of these varieties I think are horrible, useless,” he said of the pears he has been trialing, “and some are amazing and totally should be grown much more widely.”

June’s Pear is among his favorites, for its good health, pest-resistant and delicious fruit.

“We got fruit for the first time last year off the tree,” he said. “It was large. It had quite a leathery skin, but the flesh is incredible. It was melting, sweet, aromatic. The fruit is just stunning.”

In fact, at least one pest clearly likes June’s Pear – the porcupine. At her farmhouse with the original tree, LaCombe has encircled the trunk with spiky, metal porcupine guards. She’s added a large aluminum shield for good measure, hoping to prevent the pear-loving rodents from clambering up the 40-ish-foot-tall tree, gorging on its tender young branches and taking exploratory bites from much of its fruit.

Also, there is one pear variety that Cormier got from the Corvalis pear repository last spring with no previous ties to Maine, at least that she knows of. “It’s a very old French perry pear,” she said. “To be honest, I don’t know if it was ever grown in Maine, but I wanted to get it established here because it is very popular in Normandy (France) for high-quality perry, and I thought, ‘Oh, this would be fun!’ ”

June LaCombe designed a stone wall to partly encircle her beloved heirloom pear, lining it with impatiens. The pear variety has been provisionally named for her, as June’s Pear. “If you are going to get something named after you, a pear tree is a good thing,” LaCombe said. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

DNA DATA

In early September, Cormier got back results from the latest batch of trees, 10 total, that she’d had DNA-tested. (You cannot, by the way, try this yourself if you’re curious about an old tree in your backyard; the USDA station in Corvalis does not test trees from individual homeowners.) There were a few disappointments, or perhaps just surprises.

A tree at the historic Jonathan Fisher house in Blue Hill was thought to be a rare (in New England) St. Germain, or pound pear. There was good reason to think so. The Farnsworth Museum in Rockland has a map of the old pear orchard in its collection, and it says St. Germain right there on the map.

But DNA doesn’t lie. The tree turned out to be a Clapp Favourite.

“I haven’t told them the news yet,” Cormier said on a spectacular late summer morning. “It’s very common. It’s one of the most common summer pears.”

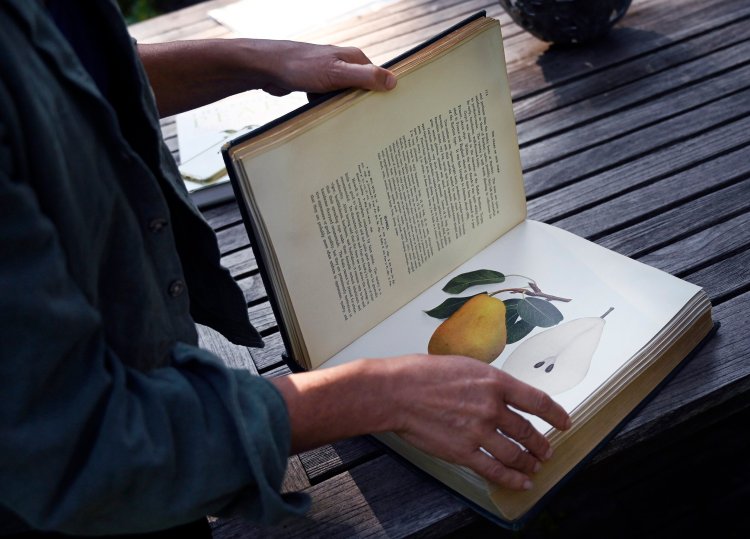

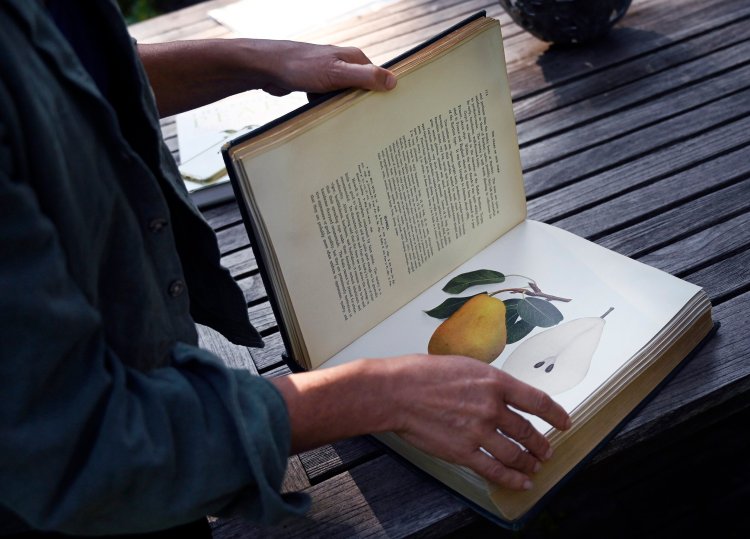

Lauren Cormier, MOFGA pear specialist and orchard assistant, flips through the book “The Pears of New York,” at Hawk Ridge Farm. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

Two other trees also came back as Clapp Favourite pears, one from Hallowell a tree she’d hoped might be a Louise Bon d’Avranches. She’d examined the fruit herself but had failed to correctly identify it.

“I felt a little unfortunate about my own ID skills,” Cormier said ruefully.

Identifying a pear by phenotypical traits, as it is called, requires meticulous observation of stem size, blush, flesh color, calyx and lobe configuration, core lines and more, and then comparing those observations to historical descriptions and old botanical prints in books — more accurately, tomes — like the 600-plus page 1921 “Pears of New York;” Cormier has a treasured copy.

“Before we were doing testing, that was really all we had,” she said. “I’d spend hours looking at this pear and trying to find anything I could.”

When a tree that has been DNA-tested comes back as unique, the old-fashioned detective work — and the hunt for old trees — continues.

“Sometimes DNA just tells us what something is not,” Cormier said.

In these latest tests, a tree that Fedco had been selling under the provisional name “Tate” turned out to be a beierschmitt, a pear variety developed in Iowa more than a century ago.

“It’s good to have an actual name,” Cormier said. “That means the nursery trade will have the correct name when they sell it, and things will gradually get less confusing.”

The Oregon repository is trying to reconstruct the entire pear pedigree. As with human DNA testing, it can use results to figure out pear parentage, to understand how different varieties are related to one another. And it can use it to eliminate duplicates, identical pear types that have been selling, sometimes for decades, under different names.

While the DNA hasn’t identified June’s Pear, it has shown that the tree is an exact match for a couple of others from nearby farms in Pownal and Durham that Cormier also sent to be tested. The tree, Cormier thinks, could be a Maine pear that was started from seed, grafted locally but never made it into wider circulation.

THE FUTURE OF MAINE PEARS

Wider circulation is just what Cormier and Newman would like to see. France and Italy have a pear culture that is centuries old (Louis XIV, France’s Sun King, adored them) and in some ways akin to Mainers’ expertise in and affection for blueberries and lobster. Maybe Mainers will take to – in a way return to – pears. After all, backyard chickens have gained in popularity over the last decade, Newman said.

“Part of my hope with us getting scionwood this past year through the USDA, is for people to trial these and see how they do,” Cormier said. “I would love to see these get dispersed throughout the state, and potentially make their way into home orchards and maybe even commercial orchards so that we can have more diversity in our pears here in Maine.”

A nascent interest among cidermakers in perry production may help, if not for these dessert pear varieties, then for pear promotion generally speaking.

Jared Carr, who owns Cornish Cider Company with his wife Jacqueline, has been experimenting with perry for several years. In 2015, he pressed the first batch he was actually pleased with, he said, from a wild seedling pear tree he found on his grandparents’ property. He later took seeds from those pears to plant trees in his orchard in the hopes of a steady supply of suitable perry fruit one day.

Carr described the drink as tasting like a cross between hard cider and white wine. “A little more delicate? You get some interesting flavors you don’t get with either of the others. Citrus, melon, sherbet sort of flavors.”

“It’s a rarer drink than cider,” he said, “but I think it will gain popularity in the future.”

No disrespect to cider, and no disrespect to apples, but perhaps Maine’s lost, mystery pears will gain popularity, too.

Pear Risotto with Bleu Cheese, Sage and Walnuts Photo by Peggy Grodinsky

PEAR RISOTTO WITH BLEU CHEESE, SAGE AND WALNUTS

I ran into the idea of adding pears to risotto where everyone runs into recipe ideas these days — on the internet — and I had to try it. It was as delicious as I’d hoped for. To me, risotto is much more a method than a recipe, so while I am reconstructing what I did here, the recipe is not etched in stone. Risotto takes attention, but it’s easy to make.

Serves 2 with hearty appetites

4-5 cups good-quality vegetable or chicken broth

1-2 tablespoons olive oil

1 leek, white and pale green parts sliced thin and washed well (save the dark green parts for stock)

1 cup arborio or carnaroli rice

1/4 cup white wine

Salt and pepper to taste

1/4 cup crumbled bleu cheese, or more or less depending on your preference and the strength of the cheese

1-2 peeled, cored and diced pears

1 tablespoon butter

3-4 fresh sage leaves, chopped, plus more for garnish

Handful of toasted, chopped walnuts, for garnish

Warm the broth in a medium-sized pot on the stove. Keep it at a slow simmer while you make the risotto.

Warm the olive oil in a heavy-bottomed medium saucepan. Add the leeks and cook over low heat until softened nicely, 5 to 10 minutes, stirring occasionally and adding a little water if they start to brown.

Add the rice to the pan and let it toast, stirring occasionally, 3 to 4 minutes. Add the white wine and stir until it evaporates. Now begin adding the warmed broth, a ladleful at a time. Stir often and do not add the next ladleful until the first has mostly evaporated. About halfway through the process, the rice will begin to look creamy and amalgamated. Continue to add the broth until the rice tastes creamy with just a slight bite of al dente. The risotto should still be a little soupy. Taste for seasoning, adding salt and pepper as needed.

Stir in the cheese. Fold in the pears. Stir in the butter and sage leaves. Let the risotto sit for a couple of minutes, then serve, topped with the walnuts and a sage leaf or two.

ERIN FRENCH’S CARAMELIZED PEAR & CORNMEAL SKILLET CAKE

The recipe comes from “The Lost Kitchen” by Erin French, who is a big fan of pears. “She can talk pears all day,” her husband and the company’s director of media relations Michael Dutton said when I reached out for an interview.

What does she like about the fruit?

Caramelized Pear & Cornmeal Skillet Cake (but the cake pictured did not get caramelized enough. Blame the cook). Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

“For me, pears are a funny luxury,” French said. “I think there is a thoughtfulness because if you are finding a pear, then it means that someone put thought and energy into planting that tree, letting that tree make its way and survive. It feels like this little special magical gift. It’s different from apples that you find so often growing wild.”

French hasn’t made any special effort to find unusual heirloom varieties. “When anyone calls me and says, ‘I have pears,’ I make no judgment on their variety. I’m just excited to have them at all. I’ve taken all types and all shapes. When we get the call, no questions asked, ‘just bring them immediately.’”

She planted a few trees on her own grounds two years ago, but they were too small to survive the tough winter that followed.

“I’m thinking ahead for my children. When I’m getting gone and this farmhouse is falling into the ground, those trees will be here for them,” she said. “I got discouraged and I didn’t (replace the trees) this year, but… next spring?”

Yield: 1 (12-inch) cake, serves 8-10

FOR THE PEARS

5 ripe but firm pears

4 tablespoons (1/2 stick) unsalted butter

1/2 cup sugar

FOR THE CAKE

1 cup all-purpose flour

1/2 cup stone-ground cornmeal

1 ½ teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

8 tablespoons (1 stick) unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 cup sugar

2 large eggs, at room temperature

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1/2 cup sour cream

To caramelize the pears, peel, halve and core the pears. Without cutting through the top 1/2 inch of the pear, slice each half lengthwise 4 or 5 times.

In a 12-inch ovenproof skillet, preferably cast iron, heat the butter over medium heat until melted. Put one pear half in the center of the pan, domed side down, and arrange the rest of the pear halves in the skillet (also domed sides down) so the slices fan slightly. Let the pears cook, untouched over medium heat until the sugar has turned a deep, dark golden color, 15 to 20 minutes (not easy to tell in a black cast-iron pan). Rotate the skillet if there seem to be any hot spots.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 350 degrees F.

To make the cake batter, combine the flour, cornmeal, baking powder and salt in a small bowl.

In a stand mixer or medium bowl, beat the butter until light and fluffy. Slowly add the sugar and beat again until light and fluffy. Add the eggs, one at a time, mixing well after each until well incorporated. Add the vanilla and sour cream. Slowly stir in the dry ingredients until just incorporated.

Spoon the batter over the pears in the skillet and bake until a tester inserted in the cake comes out clean, about 25 minutes (I found it takes almost double that; make sure the top, or what will be the bottom of the cake, is a deep golden brown).

Let the cake cool for just a few minutes (not too long or the sugar will set and the cake will stick to the pan!). Run a knife around the edge of the skillet, top with a large rimmed plate or platter, and, armed with oven mitts, carefully invert the cake onto the plate. Pay attention, as flipping such a large, hot cake in a heavy skillet is a little tricky.

Serve warm.

Copy the Story Link

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66e70ecb117549d1af6a6edeee2c11ba&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.centralmaine.com%2F2024%2F09%2F15%2Fthe-lost-pears-of-maine%2F&c=7790829464704225661&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-14 21:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.