On 13 July, under a clear blue sky in Butler, Pennsylvania, bullets sliced through the air piercing the ear of the former president of the United States, Donald J. Trump. While he escaped death thanks to the tilt of his head, a stray bullet fatally injured a bystander behind him. “The reality is just setting in,” Trump told the Washington Examiner the following day. “I rarely look away from the crowd. Had I not done that in that moment, well, we would not be talking today, would we?”

In the wake of this shocking event, millions are now searching for answers. How was a twenty-year-old gunman able to secure a position on a roof overlooking a presidential candidate’s rally, let alone fire off multiple rounds? On social media, security experts have highlighted operational mistakes made by the Secret Service, while political figures have blamed the media and Democrats. Meanwhile, a desperate scramble is underway to link the shooter to a coherent political motive.

However, the search for a clear political motivation may be misguided. History teaches us that some forms of extreme violence lack ideological underpinnings. To truly understand such acts, we may need to look in unexpected places.

The last attempted assassination of a US president provides a lesson. Forty-four years ago, a man named John Hinckley Jr. followed US President Jimmy Carter across multiple states, stalking him from Washington, D.C., to Columbus, and then Dayton, Ohio. Hinckley came within 20 feet of President Carter but decided at the last minute not to shoot him. That fate would await the next president, Ronald Reagan, outside the Washington Hilton hotel in an assassination attempt that left three Secret Service agents with gunshot wounds, and the President with serious injuries.

Surprisingly, this assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan lacked a clear political motivation. Hinckley was driven not by ideology, but by a delusional desire to impress actress Jodie Foster. A note he wrote prior to the shooting provides insight into his morbid fantasy:

Over the past seven months I’ve left you dozens of poems, letters and love messages in the faint hope that you could develop an interest in me. Although we talked on the phone a couple of times I never had the nerve to simply approach you and introduce myself. … The reason I’m going ahead with this attempt now is because I cannot wait any longer to impress you.

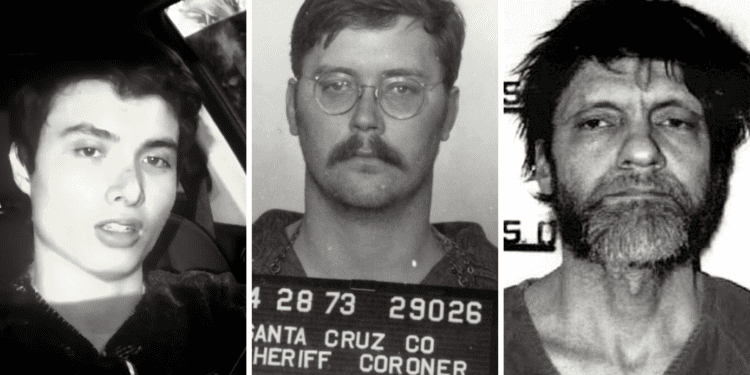

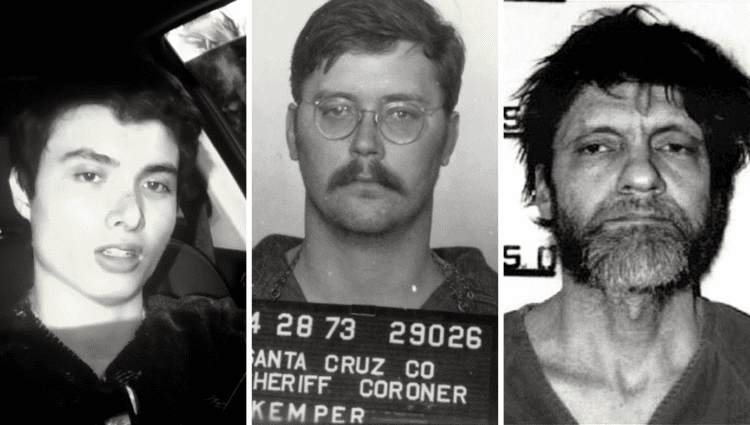

Seemingly irrational violence is not unique to Hinckley. In fact, it fits into a broader pattern identified by behavioural science. Psychologist Robert King, in a 2019 study on spree killers, wrote: “Males have been literally running amok—attacking innocent strangers en masse—across time and space.” In their study of spree killers, King and his colleague Nadia Butler analysed an archival search of 70 mass murderers, and found that they fell into two distinct groups. These groups were defined by age and stage of life. The younger killers, with an average age of 23, often had troubled pasts and mental health issues, and appeared to use violence as a way to obtain status, simply through infamy. By comparison, the older group, averaging 41 years old, were typically married with children and did not have a history of mental illness. They had recently experienced a significant loss in status, such as job loss or marital breakdown. Their primary motivation was jealousy.

Expanding on the younger group, King and Butler write:

Younger spree killers (our type 1) were at the start of their potential reproductive careers and were already showing signs that they would be unsuccessful—more likely to have been in trouble with the law and to have shown a history of mental illness. In the past, younger males otherwise on a path to reproductive oblivion might have been motivated to a public display of prowess—perhaps in raids or battle…. the incident for the younger killers may function as an attention-seeking event, an effort to garner a reputation and achieve idol-like status.

This pattern is evident in numerous high-profile cases. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the Columbine High School shooters, were 18 and 17 respectively when they committed their massacre in 1999. They were known social outcasts who had been subjected to frequent bullying. Adam Lanza, only 20 years old when he perpetrated the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012, was profoundly socially isolated and suffered from significant mental health issues. Elliot Rodger, 22 at the time of his 2014 Isla Vista killings, published a manifesto detailing his sexual frustrations and hatred of women. Seung-Hui Cho, the 23-year-old Virginia Tech shooter, had a history of severe anxiety and selective mutism. Nikolas Cruz, who killed 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018, was 19 and had a history of behavioural and emotional problems. James Holmes, the Aurora theatre shooter, was 24 and was likewise suffering from mental illness and social isolation. Salvador Ramos was 18 when he fatally shot 19 children and two teachers at the Uvalde school shooting.

The Status Game: Male, Grandiose, Humiliated

The logic of the status game dictates that humiliation must be uniquely catastrophic.

In the realm of political assassinations, we see a similar pattern of youth typically combined with mental illness or emotional disturbance. John Hinckley Jr. was 25 years old, with no job and no girlfriend, harbouring delusions of forming a relationship with Jodie Foster. Lee Harvey Oswald, who assassinated John F. Kennedy, was a 24-year-old with a history of violence, paranoia, and social rejection. Sirhan Sirhan was 24 when he killed Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, reportedly motivated by Kennedy’s support for Israel. John Wilkes Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, was just 26.

In an article for Quillette published last year, Robert King observed that “mass killings are, among many other things, a deliberately public, attention-seeking attempt to drive a wedge into the existing social order.” In 2024 America, what could be more attention-seeking than attempting to kill Donald Trump?

To understand the dynamics of male social hierarchies, we need look no further than the target of yesterday’s assassination attempt—Donald J. Trump. Trump’s political ascendancy has disrupted the established order in the United States, largely because he exhibits qualities such as aggression, defiance, and individualism—traits traditionally associated with dominant status within a male social pecking order.

Donald Trump and the Failure of Mainstream Social Science

Many social scientists have quite openly voiced surprise and perplexity at both the Trump and Brexit events

This brings us to a crucial point: while our modern, civilised societies ostensibly prioritise qualities like compassion, integrity, and empathy, and while we no longer reward brute force with status, our evolved psychology means that we remain sensitive to displays of male dominance, even when doing so conflicts with our professed values.

While our societal values have evolved to emphasise qualities such as diversity and inclusion, our deep-seated responses haven’t entirely caught up. This is evident in our enduring fascination with hero narratives in literature and film, and the popularity of violent entertainment. Despite all the cultural influences telling us that masculinity is toxic, many of us still possess an alertness for traits that have historically enabled male sex to conquer adversaries.

In other words, there is, at times, a dichotomy between our espoused values and our instinctive responses: the Superego and the Id. On one hand, we celebrate intellectual achievements, ethical behaviour, and emotional maturity. On the other hand, we find ourselves captivated by displays of raw courage, physical strength, and social dominance—even when these displays run counter to our stated ideals.

Trump’s political success and the visceral reactions he elicits—both positive and negative—reflect this tension. His defiance of political norms taps into a primal understanding of dominance that resonates with many, even as it repels and repulses those who prioritise leadership qualities that are more sophisticated and refined.

The irony is that in trying to assassinate Donald Trump, Crooks inadvertently provided Trump with an opportunity to display the very qualities that have already made him a cult icon. Trump’s immediate reaction—standing up and raising his fist to the crowd despite the clear and present danger—exemplified the kind of raw, physical courage that our evolutionary programming associates with effective leadership and high status.

Surviving an assassination attempt has historically been a powerful way for leaders to cement their legacy and elevate their status to hero-worship levels. Ronald Reagan’s popularity soared after he survived Hinckley’s attempt on his life. And Fidel Castro’s repeated survival of CIA plots similarly added to his legendary status among his supporters.

In Trump’s case, this event may well transform him from a controversial political figure into something approaching an American folk hero. The narrative writes itself: the “outsider” president, constantly under metaphorical fire from the establishment, has now come under physical fire—and remained unbowed. It’s a story that fits perfectly into the heroic archetype that humans have celebrated for millennia.

Crooks’ attempt to gain status through violence has backfired spectacularly. Instead of achieving infamy, he has been relegated to a footnote of history. His action, far from disrupting the existing social order, has reinforced it by not only elevating Trump’s status but also increasing his likelihood of winning the next US election.

In Season 1, Episode 8 of classic American crime drama The Wire, legendary gangster Omar Little utters the immortal line: “You come at the king, you best not miss.” Omar’s words underscore the cruel truth about violence as a means of status-seeking: it often backfires, reinforcing the very hierarchies it seeks to challenge. In this case, a man with no status has, through his actions, helped elevate his target to a status so high it borders on the mythic—a leader who can defy not just his political opponents, but death itself.

Source link : https://quillette.com/2024/07/15/courage-and-cowardice-in-pennsylvania-donald-trump/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-15 05:20:08

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.