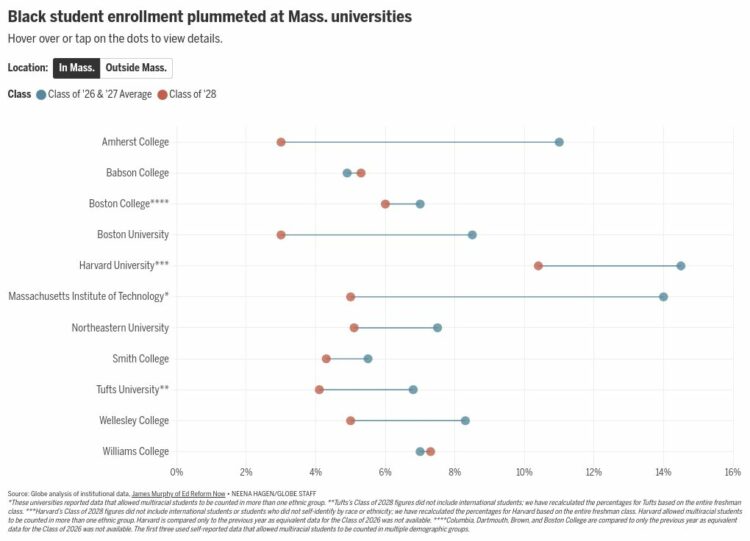

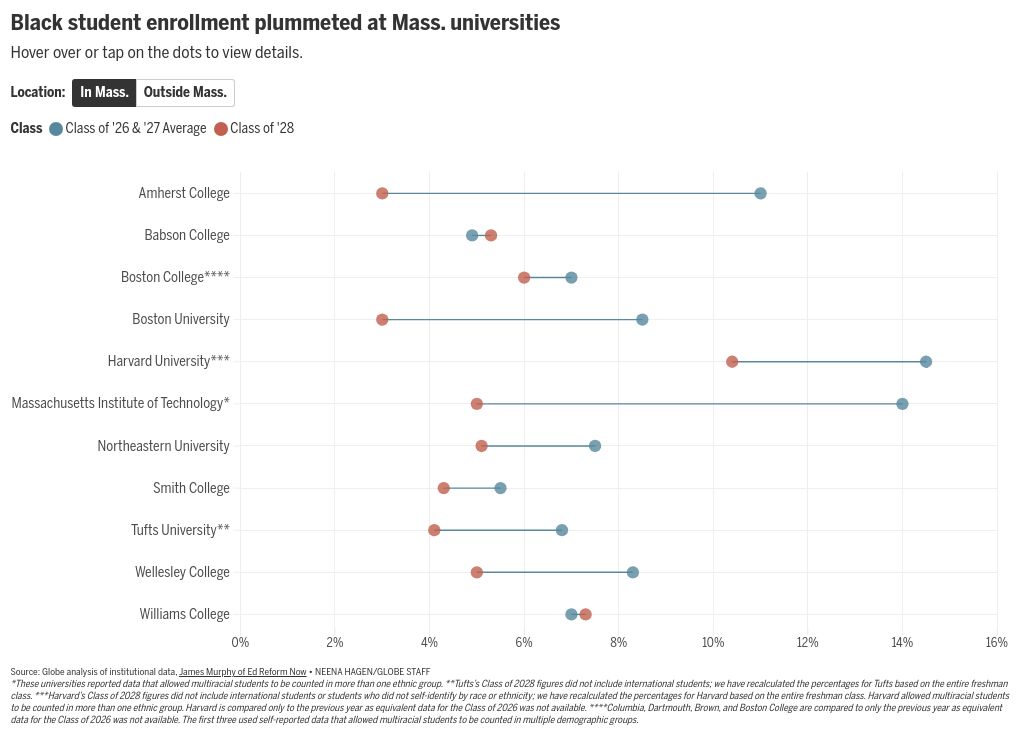

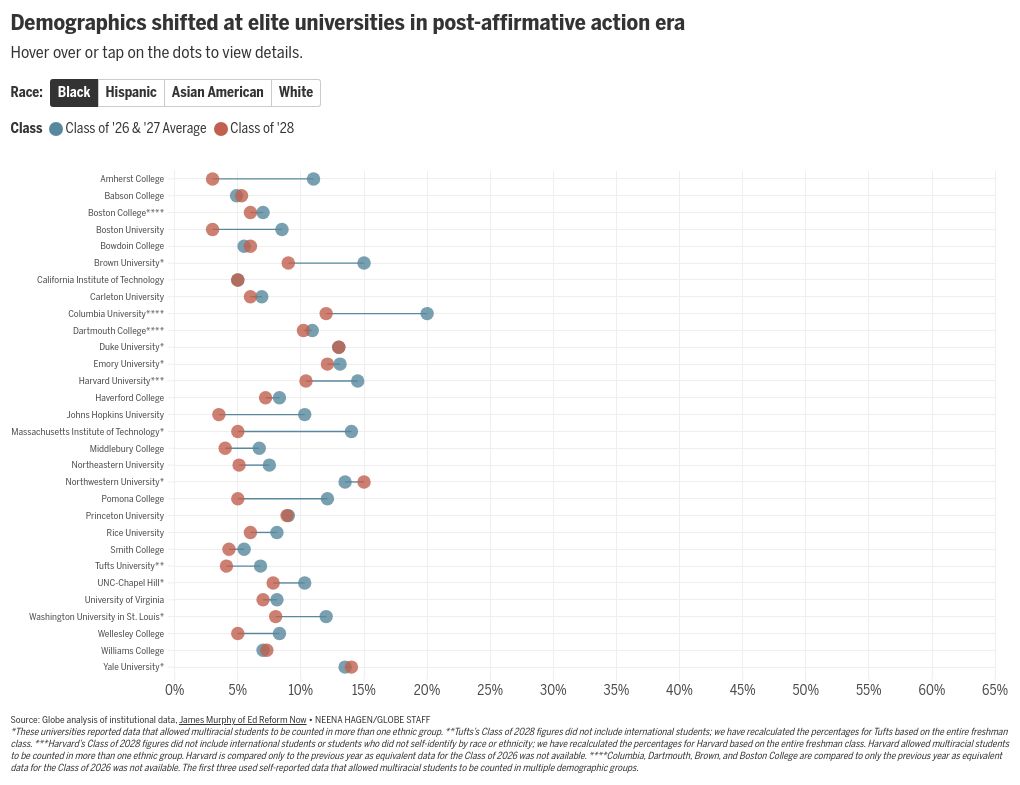

The share of Black first-year students this year fell from 11 percent to 3 percent at Amherst College; from 14 percent to 5 percent at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; from 8.5 percent to 3 percent at Boston University; and from 14.5 percent to 10.4 percent at Harvard University.

Harvard earlier this month reported Black students make up 14 percent of current first-year students, down from 18 percent last year, but these figures do not include international students or students who withheld their racial identity. The Globe recalculated the figures for Harvard to include both groups.

The end of affirmative action has not so far led to significant increases in white first-year enrollment, as some expected. The 30 schools in the Globe’s nationwide analysis reported a slight decline — of less than 1 percentage point, on average — in the share of white students enrolled in the first-year class. Across the top 11 Massachusetts schools, the share of white students barely budged.

Asian American students appear to have benefitted the most from the affirmative action ruling. The share of Asian American first-year students increased, on average, 1.4 percentage points across 30 schools nationwide, data show. Students for Fair Admissions, the group that brought cases against Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to the Supreme Court, alleged the universities discriminated against Asian Americans in the admissions process.

The share of Hispanic first-year students declined about 1 percentage point across the 30 schools.

Research has found that private, highly selective colleges — which have historically been among the least diverse, and have been trying to change that over the last several decades — were the most likely to consider race as one factor in the admissions process before the court’s ruling last summer. Less competitive colleges, especially those that accept more than 50 percent of applicants, can’t afford to be as choosy, and so are less impacted by the ruling, the Pew Research Center found last year.

Several higher education watchers cautioned the data are preliminary, and it may be too soon to identify trends with information from just one year. More students this year also declined to disclose their race. Still, some scholars and advocates say they are concerned about this year’s declines in Black enrollment.

“It is heartbreaking,” said Anthony Abraham Jack, a Boston University professor who studies first-generation students and is a graduate of Amherst College. “It is leading to the segregation of higher education. You will see top schools get whiter and wealthier.”

Jack said he worries about the long-term effects of fewer Black students attending top colleges.

“This will fundamentally restrict the ability to have people heading our most powerful institutions look like America, and not just the wealthier, whiter 1 percent,” Jack said.

The MIT Black Students’ Union and Black Graduate Students’ Association said in a statementthey “are deeply concerned by the newly released demographic data for MIT’s Class of 2028.”

“While imperfect, affirmative action was instituted as a tool to help combat the centuries of structural racism — slavery, Jim Crow segregation, redlining, mass incarceration — that continues to systematically keep Black and other minoritized people out of higher education,” the student groups wrote.

MIT blamed its decline in first-year students of color on “persistent and profound racial inequality in American K-12 education,” Stu Schmill, MIT’s dean of admissions and student financial services, wrote in a blog post last month.

Leaders at Amherst College, which posted significant declines of both Black and Hispanic first-year students, said in a letter to its community last month they were determined to “continue and deepen” efforts to recruit diverse students “in accordance with the law.”

“This process will take time, but we are very confident that we will continue to build a community that reflects the diversity of the world around us,” Amherst leaders wrote.

Natasha Warikoo, a professor of sociology at Tufts University, who has written extensively about affirmative action in college admissions, said the share of students of color in states that previously banned affirmative action dropped precipitously in the first few years after respective bans and then started to rebound. She added it’s “not a surprise” to see inconsistent enrollment numbers posted across colleges that consider many factors in the admissions process.

The Supreme Court’s ruling did not end holistic admissions policies, in which top colleges consider a range of factors beyond academics, including applicants’ life experiences, challenges overcome, and family or work obligations. Many colleges added essay questions in response to the ruling to allow prospective students to share context about their lives. Schools also said they increased outreach efforts to more high schools and partnered with more community groups and nonprofits to reach first-generation students, low-income students, and students from rural settings.

The Supreme Court cautioned that schools should not rely too much on work-arounds to “establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.”

It is unclear at this point why Black first-year enrollment fell at a majority of schools while holding steady at a handful of others, including Princeton University, where Black first-year enrollment held roughly steady, and Yale University, where Black first-year enrollment grew half a percentage point. A spokesperson for Yale said its pool of applicants for the incoming class “was the largest in Yale’s history and included the most applications ever from students who identified as members of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.”

Students for Fair Admissions earlier this week said it would investigate whether Yale in New Haven, Princeton in New Jersey, and Duke University in North Carolina are complying with the Supreme Court’s ruling. SFFA argues that “it is not possible for these schools to obtain the racial outcomes for the class of 2028 that they have reported without using racial proxies that the Supreme Court forbids.”

“SFFA hopes these colleges will provide us and the public with specific, granular details about their new admissions policies,” Edward Blum, president of SFFA, said in a statement.

A spokesperson for Princeton did not respond to requests for comment.

A spokesperson for Duke said the university is “committed to compliance with the law.” A spokesperson for Yale said its “admissions practices fully comply with the law and the Supreme Court’s 2023 ruling.”

Warikoo said Students for Fair Admissions’ concerns about Duke, Yale, and Princeton “are nonsense.”

“I don’t think those cases are going to go anywhere, but it is disturbing how much they are invested in their crusade against racial justice,” Warikoo said.

Universities do not use consistent methods to report their data, which complicates the early analysis of the admissions numbers. Five schools — Harvard, Boston College, Carleton, Middlebury, and Haverford — did not report the share of white students in the class of 2028. Eleven schools, including MIT, allowed multiracial students to be counted in multiple demographic groups, which could appear to boost the number of students of color. Other schools, such as Tufts, calculated percentages without including international students. The Globe recalculated Tuft’s percentages to include international students.

Some higher education watchers said they hope the declines in Black first-year student enrollment will prompt discussion about how to increase access to top colleges.

James Murphy, director of postsecondary policy at Education Reform Now, a nonprofit think tank, said the drop in students of color at schools such as Amherst and MIT were particularly “painful” because those institutions have made significant investments in diversifying their student populations in recent years, and neither school uses legacy preferences, which give priority to children of alumni.

Murphy, who created an online tool to track enrollment outcomes after the Supreme Court ruling, said the results at MIT and Amherst are a reminder that doing away with legacy preferences is not a “panacea,” but he still hopes that top schools will reconsider long-held practices such as recruiting large numbers of students from prestigious private high schools, and giving big boosts to athletes.

“I hope this is another spur to getting rid of those practices,” Murphy said.

Hilary Burns can be reached at hilary.burns@globe.com. Follow her @Hilarysburns. Neena Hagen can be reached at neena.hagen@globe.com.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66f3fbbf5b4c4e44a187bb95bbcecc04&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bostonglobe.com%2F2024%2F09%2F25%2Fmetro%2Faffirmative-action-colleges-black-enrollment%2F&c=13653330922017196632&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-25 00:42:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.