“I can’t believe it’s pink!”

That’s not quite the slogan made famous by the margarine known as “I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter.”

However, it could have been as Minnesota once came out swinging in defense of the state’s dairy producers. Starting in 1895, the state used legal measures to dissuade consumers from buying margarine, at one point dying the product an unappetizing shade of pink somewhere between Easter Bunny and Barbie.

The plan — which included measures to make margarine cost more and look less like real butter — spread to neighboring North Dakota, the other of the final two holdouts in the Great American Butter Battle.

It all began in 1867, when Emperor Napoleon III offered a prize to anyone who could find a substitute for expensive and hard-to-find butter. Chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès walked away with the prize for his creation of oleomargarine (later known as just oleo or margarine), which combined beef fat and milk into a spread similar to butter.

French chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès developed a process for turning beef fat and milk into a spread that tasted like butter and called it oleomargarine.

Contributed / Public Domain Illustration

By 1873, Mège-Mouriès had received a U.S. patent for the oleomargarine manufacturing process.

The Minnesota Historical Society noted margarine’s arrival in the United States coincided with the country’s shift from an agricultural to an industrial economy.

“Many farmers worried that products made in laboratories and factories would replace traditional agricultural goods. Oleomargarine, with its similarities to butter, seemed like a particularly ominous threat. Dairy organizations throughout the country began lobbying Congress and state legislatures to pass protective anti-margarine laws,” according to a journal article published in

MNopedia.

Minnesota comes out swinging

By 1885, Minnesota became one of the first states in the Union to prohibit the production and sale of oleo. Governor Lucius Hubbard called margarine “an abomination.”

The following year, a federal law determining margarine as a legal product invalidated the Minnesota law.

In 1885, Minnesota Governor Lucius Hubbard announced that sales of “oleomargarine and its kindred abominations” would cease in the state.

Contributed / National Governor’s Association

Over the coming years, intense legal battles between pro and anti-margarine factions unfolded, with each side continuously responding to the constantly evolving rules and regulations.

In 1891, Minnesota dairy leaders convinced the state legislature to pass pink laws, requiring any oleo produced in the state to be dyed pink.

“Since few consumers relished the idea of slathering a pink, butter-like spread on their toast, the pink law effectively halted all sales of oleo in the state in the 1890s,” said the Minnesota Historical Society.

Margarine moguls fought back, taking their case to the Supreme Court, which, in 1898, ruled that pink laws were unconstitutional.

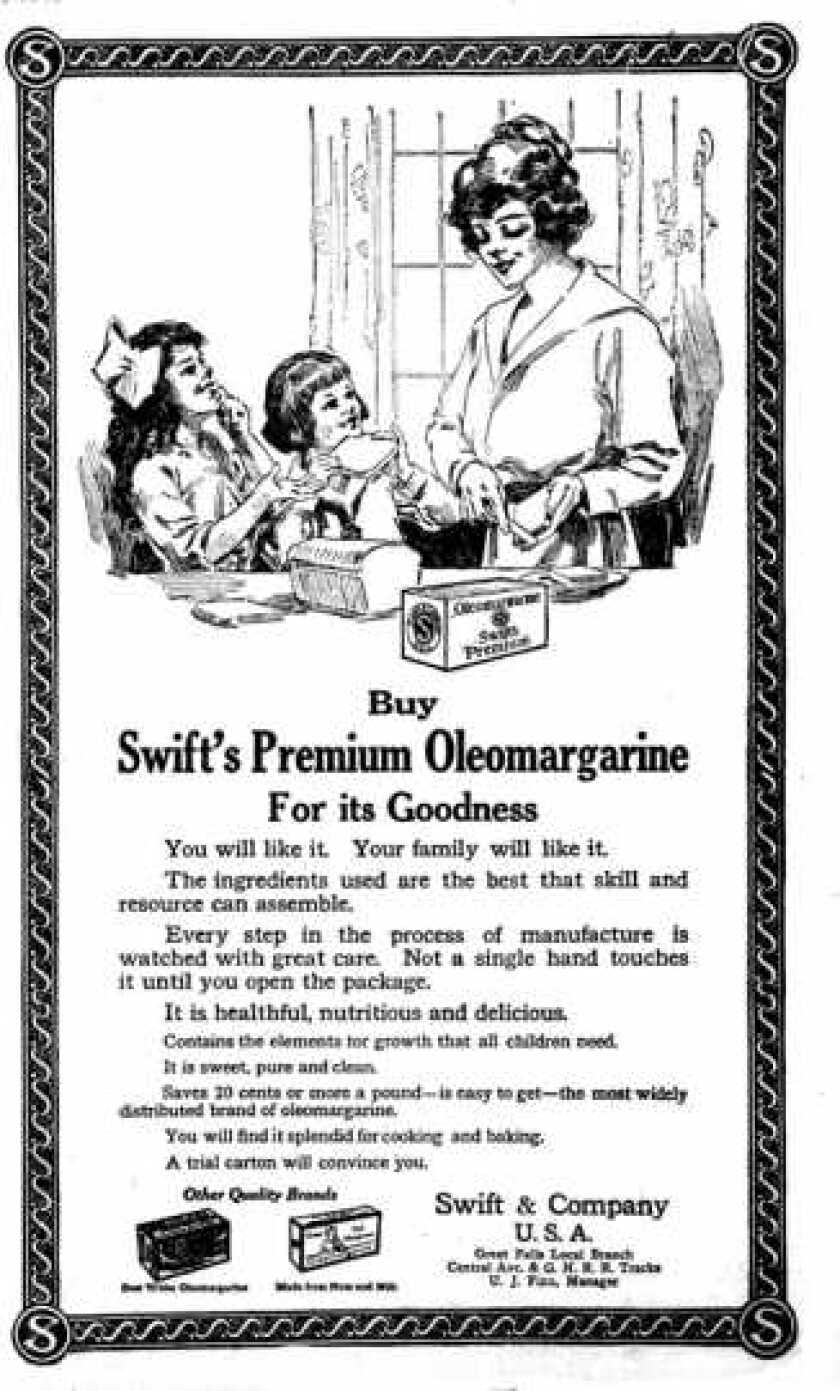

Dairy producers found the patent of oleomargarine a serious threat in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Contributed / Minnesota Historical Society

With margarine now de-pinkified, producers started dying it yellow to make it look more like butter. However, dairy producers scored a major victory in 1902 when the federal government put higher taxes on the yellow-tinted margarine versus the natural white product.

Dairy producers said yellow-dyed margarine amounted to fraud, as manufacturers hoped to fool consumers into thinking they were eating real butter. Margarine makers said proper labeling of their products ensured people weren’t being fooled.

In the ’70s, Mother Nature was fooled by margarine

According to the Minnesota Historical Society, oleo proponents got around the color issue in a new way.

“During the 1910s, (margarine makers) started packaging white margarine with packets of artificial food coloring so that consumers could knead it in by hand.”

The butter battle continued into the mid-century. However, by 1950, the federal government repealed its long-standing tax on margarine largely because most margarine was now produced using vegetable oils provided by American farmers.

However, the states of North Dakota and Minnesota weren’t quite ready to give margarine companies carte blanche. The two states continued to tax margarine well into the 1960s.

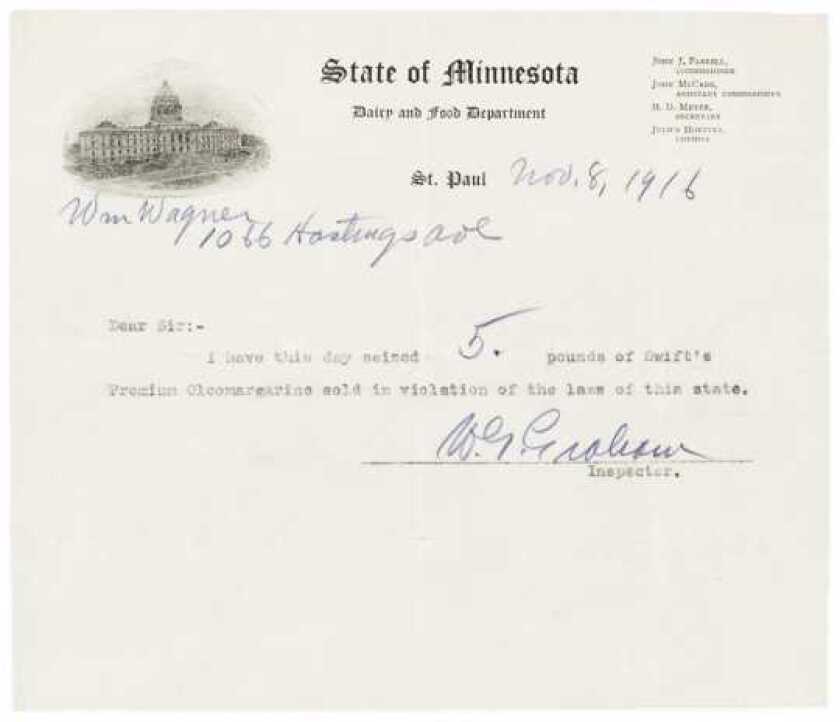

State officials cracked down on bootleg butter the same way they cracked down on moonshine during Prohibition.

Restaurants were written up for the use of illegal margarine.

Contributed / Minnesota Historical Society

“Among the unlucky scofflaws was the owner of a Scandinavian restaurant in Minneapolis who was caught serving lutefisk with an illegal mixture of melted yellow oleo and butter,” according to The Minnesota Historical Society.

Did mixing oleo and butter make lutefisk taste better? Maybe.

Either way, the Great American Butter Battle finally ended in Minnesota and North Dakota on July 1, 1975, when margarine taxes expired leaving Minnesotans and North Dakotans forever free to spread whatever they wanted — pink, yellow, high-taxed or low-taxed — on their morning toast.

Tracy Briggs has more than 35 years of experience, in broadcast, print, and digital journalism.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66e204eac8a640f091ee155a040aa22d&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.grandforksherald.com%2Fnews%2Fthe-vault%2Fwhy-was-minnesotas-and-north-dakotas-margarine-once-pink&c=54352398226157022&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-11 09:59:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.