On August 19, the U.S. Treasury Department announced an agreement with China to promote cooperation on financial matters. Treasury reported that the Fifth Meeting of the Financial Working Group with the People’s Bank of China, China’s central bank, had “concluded with the Treasury and the PBOC exchanging letters in support of coordination during times of financial stress to strengthen appropriate information sharing and reduce overall uncertainty between Treasury and the PBOC regarding crisis management and recovery and resolution frameworks.”

“The two sides,” Treasury stated, “also exchanged key points of contact to make it easier to quickly coordinate in instances of financial stress or operational resilience issues.”

Is Washington preparing to bail out a struggling China?

Beijing doesn’t think it needs one. “Chinese Economic Collapse Not Happening,” a China Daily headline from August 29 states. But assurances from Chinese propagandists have not alleviated concerns around the world. As the New York Times reported this month, “China’s economy is confronting a crisis unlike any it has experienced since it opened its economy to the world more than four decades ago.”

The crisis is evident most everywhere. More than a million restaurants in China closed since the beginning of this year, according to Canguanju, a news service for China’s catering industry. “Chinese Offices Emptier Than During Covid Pandemic as Slowdown Hits,” a Financial Times headline from late last month tells us. In the all-important property sector, the value of new home sales of the 100 biggest developers fell 26 percent year-on-year in August, steeper than July’s 19 percent drop. Duty-free sales in Hainan Island, a major tourist destination, in the first seven months of the year plunged 30 percent. Summer box office revenue is down 44 percent from last year.

With other signals pointing in the same direction and with downward momentum accelerating it’s hard to see how China’s economy can be growing at the 5 percent pace officially reported for the second quarter of this year.

No matter how fast it’s growing, China does not appear to be producing sufficient output to service indebtedness. As a result, the country is now reliving 2008, perhaps in slow motion but 2008 nonetheless.

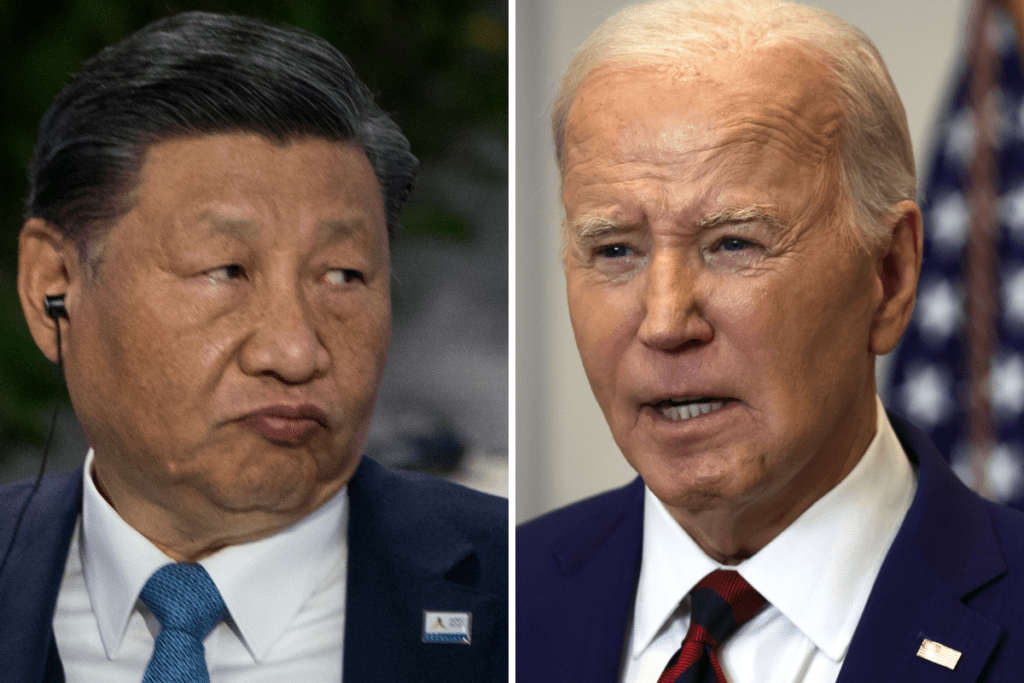

Chinese President Xi Jinping is seen during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders’ Informal Dialogue with Guests during APEC Leaders’ Week at Moscone Center on November, 16, 2023 in San Francisco, California. President Joe Biden…

Chinese President Xi Jinping is seen during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders’ Informal Dialogue with Guests during APEC Leaders’ Week at Moscone Center on November, 16, 2023 in San Francisco, California. President Joe Biden delivers remarks on the collapse of Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, Maryland, in the Roosevelt Room of the White House on March 26, 2024 in Washington, DC. On Tuesday, Biden spoke with Xi by phone for the first time in nearly two years.

More

Kent Nishimura/Alex Wong/Getty Images

Beijing overstimulated its economy to get past the 2008 global financial crisis. Chinese leaders created growth then, but they made the country overly dependent on government spending, building, among other things, too many apartment blocks, skyscrapers, and high-speed rail lines.

And they incurred too much debt. China’s total-country-debt-to-GDP ratio, after taking into account the so-called “hidden debt” and adjusting for inflated GDP reports, could be, according to my estimate, 350 percent.

China claims its policies are “pragmatic,” but that is hard to believe. Almost every analyst, economist, and observer says China must now focus on consumer spending, but China’s regime is geared to depressing consumer sentiment. For instance, deposit interest rates at banks have been kept artificially low to support state lending for uneconomic projects now scarring the country. Furthermore, the nationwide hukou system of household registration, which prevents rural Chinese from obtaining residency in urban areas and thereby earning higher wages there, also undermines consumer spending.

Xi Jinping is continuing to build industrial capacity even though China’s factories produce far more than the Chinese can consume. As Council on Foreign Relations fellow Zongyuan Zoe Liu writes in the current issue of Foreign Affairs, Beijing’s policies are currently aggravating the overcapacity problem, not mitigating it. As a result, the phrase “doom loop,” as applied to China’s economy, is now becoming popular.

This means China’s only way out is to continue to export to the world, but as Nobel laureate Paul Krugman points out, the world does not have the capacity to absorb China’s products.

Why is Xi continuing with an unsustainable plan? By bolstering manufacturing, he is pleasing core Communist Party constituencies, helping struggling state banks and building China’s capacity to wage war. Moreover, the Party now believes, as Liu of the Council on Foreign Relations notes, that “consumption is an individualistic distraction that threatens to divert resources away from China’s core economic strength: its industrial base.”

“Chance of structural reform?” Anne Stevenson-Yang of J Capital Research USA asks. “None.”

No real reform means China has a near-zero chance of avoiding a financial crisis. As President Joe Biden said in August of last year at a private event for Democratic Party donors in Salt Lake City, China is a “ticking time-bomb.”

So how should we think of the Treasury’s August 19 agreement?

In one sense, the pact looks routine. As Stevenson-Yang, also author of Wild Ride: A Short History of the Opening and Closing of the Chinese Economy, tells me, “it has nothing to do with bailing out China.” “The U.S. has not in any way said it will provide financial assistance.” The agreement, she says, “just means we know the U.S. and Chinese economies are linked to a degree and if China does get into some sort of crisis, we’d like early warning.”

She is correct, but Roger Robinson, former chairman of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, focuses on the symbolism of the August 19 agreement. “The signals sent by the bilateral Financial Working Group scream Treasury-led bailout preparations, the exact opposite of, for example, properly closing off Chinese access to the U.S. capital markets and private equity flows for American-sanctioned Chinese companies and other corporate bad actors,” he told me.

At a time when the world is looking to the U.S. for leadership on China, Washington should not, as Robinson argues, give any indication that the U.S. supports the maintenance of the dangerous Chinese regime as it moves in especially troubling directions.

Whatever Treasury is trying to do with the August 19 agreement, America needs to quickly reassess relations with China. “The Chinese Communist Party’s primary vulnerabilities lie in its current economic weaknesses, including the possibility of significant financial instability,” Jonathan Ward, author of The Decisive Decade: American Grand Strategy for Triumph Over China, wrote to me this month. “While some may see the Financial Working Group as a confidence-building measure that can create stability in the U.S.-China relationship, Washington should not provide a lifeline to this adversary.”

Three times in the past—in 1972, 1989, and 1999—American presidents saved Chinese communism. Whatever the wisdom of the policies then, at this moment, as Maria Bartiromo puts it, the U.S. should not be “Underwriting the Enemy.”

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China and the upcoming Plan Red: China’s Project to Destroy America. Follow him on X @GordonGChang.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.

Source link : https://www.newsweek.com/biden-administration-preparing-bail-china-out-opinion-1949893

Author :

Publish date : 2024-09-06 02:38:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.