The 213th Field Artillery Battalion, B-Battery’s full complement of M7 105mm self-propelled howitzers during the Battle of Kapyong, 1951. Photo shot by Lloyd Cannon, a member of B-Battery, and provided courtesy of Lloyd Cannon family, St. George News

ST. GEORGE — Amid the chaos of battle, a soldier’s memory crystallizes and soon becomes a fragment of time etched in the crucible of war.

In a poignant letter home, penned by an anonymous member of the United Nations forces in Korea, dated 1951, and discovered in the National Archives, a personal account of the war comes to life. The writer’s words, written in the midst of conflict, offers a unique perspective on the experiences of those who served in the Korean War.

As the sun dipped low in the sky, casting long shadows over the fallen, men wiped blood from their faces and steeled their nerves for the next enemy charge. From battle lines separated by miles, yards, and inches, the battlefield stretched before the men – a canvas of agony and valor — an anonymous member of the U.N. force

Little more than a year after the war had begun, the Chinese, with support from North Korea, launched their spring offensive to retake the city of Seoul. During the first phase of the attack on April 22, 1951, enemy troops quickly overran South Korean forces defending a major approach route into the capital.

The Chinese push occurred on two broad fronts. The main thrust across the Imjin River in the western sector involved 337,000 troops driving towards Seoul and the secondary effort of 149,000 troops attacking further east across the Soyang River. A further 214,000 Chinese volunteer troops supported the offensive.

Facing the Chinese troops were 418,000, well-trained U.N. troops who enjoyed greater firepower and air superiority making them a very potent fighting force.

In the U.N.’s favor was the Chinese battle strategy that used “human wave” tactics, which were effective when they entered the war in December 1950, but by 1951, the U.N. forces learned that they could deal with the tactic and were no longer overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of Chinese soldiers attacking in force.

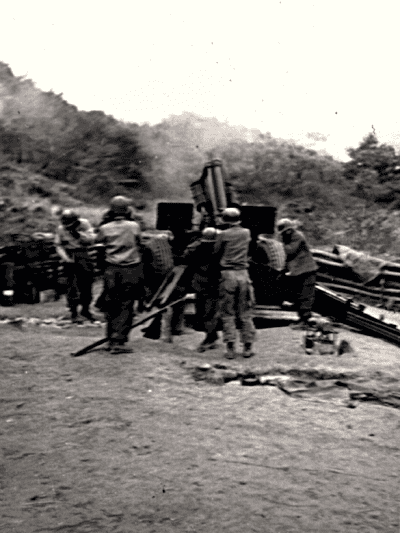

Members of the 213th Armored Field Artillery Battalion from Southern Utah sending steel on target during the Battle of Kapyong. Utah had five battalions of the National Guard called up during the Korean War. Units came from throughout the state: Beaver, Richfield, Fillmore, St. George, Cedar City, Logan, Smithfield, Garland, Brigham City, Salt Lake City, Provo, Pleasant Grove, Nephi, Mount Pleasant and Spanish Fork. Date undefined | Photo courtesy of the Utah National Guard 2-222nd Field Artillery, St. George News

Members of the 213th Armored Field Artillery Battalion from Southern Utah sending steel on target during the Battle of Kapyong. Utah had five battalions of the National Guard called up during the Korean War. Units came from throughout the state: Beaver, Richfield, Fillmore, St. George, Cedar City, Logan, Smithfield, Garland, Brigham City, Salt Lake City, Provo, Pleasant Grove, Nephi, Mount Pleasant and Spanish Fork. Date undefined | Photo courtesy of the Utah National Guard 2-222nd Field Artillery, St. George News

The initial encounters involved a sequence of enemy scouting patrols that tested the U.N. defenses.

At first, South Korean forces, the 6th Republic of Korea (ROK) Division, engaged in the battle, but soon crumbled under the Chinese assault, retreating chaotically for 18 miles south before trying to regroup.

The battle for control of the ridge high above the Kapyong Valley intensified.

To support the beleaguered South Korean soldiers were units from the 27th Commonwealth Brigade, consisting of British, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand soldiers. The 213th was also in the mix and provided artillery support to the 6th ROK and Commonwealth troops.

“I was witnessing a rout,” said Capt. Owen R. Browne, commanding officer of the Princess Pat’s A Company, Canadian 16th Field Artillery Regiment.

“The valley was filled with men. …Some killed themselves on the various booby traps we had laid, and that component of my defensive layout became worthless. Between (3:30 p.m.) and 6 p.m. all of A Company sped up its defensive preparations and digging in as it watched, helpless to intervene, while approximately 4,000 – 5,000 troops (from the 6th ROK Division), fled in disorganized panic across and through the forward edges of the U.N. positions. But we knew then that we were no longer 10-12 miles behind the line; we were the front line,” Browne added.

Although heavily outnumbered, the U.N. held their positions into the afternoon of April 24, before they retreated to a reserve position near their brigade headquarters. That day, both sides suffered heavy casualties.

“The Korean line had collapsed and then the Chinese 60th Division came swooping down into the canyon from the north. It was here that the 213th as well as the 27th Commonwealth troops and the U.S. 72nd Heavy Tank Battalion fought a running retreat for about four days between April 22 – 26,” said Dodge Billingsley, military historian and defense analyst for the U.S. Army who is currently producing a documentary film about the 213th in Korea.

By April 29, the Chinese Spring Offensive was halted by U.N. forces at a defensive line north of Seoul.

Although the main blow had fallen on the U.S. I Corps, the resistance by British Commonwealth forces in the battles at the Imjin River and at Kapyong helped blunt the attack and prevented a potential encirclement of I Corps. The Chinese had now nearly exhausted their resources of men and material and were approaching the limit of their supply lines.

In mid-May, the Chinese launched the second phase of the Spring Offensive, a concerted effort to regain momentum. However, U.S. counterattacks proved successful, recapturing lost territory and pushing forward with haste.

During their swift advance, U.N. troops unintentionally trapped a Chinese division, effectively severing their escape routes.

Around 2 a.m. – May 27, 1951 – The encircled Chinese forces attempted a breakout, charging directly through the 21st Infantry Regimental headquarters, the regiment’s medical field hospital, and A Battery of the 213th. This bold maneuver brought intense combat right to the doorstep of the Utah soldiers, with A Battery bearing the brunt of the fighting, Billingsley said.

In the ensuing battle, which raged until dawn, a valiant group of 225 soldiers from the 213th – men from Cedar City and Richfield – fought off approximately 3,000 – 4,000 Chinese who were attempting to get back across the front line and rejoin their troops.

Military records recount the terrifying moments of battle.

“During the early morning hours of 27 May, the hostile force suddenly open fire … All available men … were immediately deployed in defensive positions. The enemy fought fiercely to break their way through the valley but despite the necessity of hand-to-hand combat, the artillerymen held their ground which enabled their comrades to continue firing missions in support of the distant infantry.”

According to the U.S. National Archives, more than 140 Utah soldiers, including 1st Lt. Lavon Martineau, Cpl. Walter A. Morrison and Cpl. Walter V. Jensen from Washington County, Utah, lost their lives during the Korean War. Circa 1951, location undefined | Photo courtesy National Archives, St. George News

According to the U.S. National Archives, more than 140 Utah soldiers, including 1st Lt. Lavon Martineau, Cpl. Walter A. Morrison and Cpl. Walter V. Jensen from Washington County, Utah, lost their lives during the Korean War. Circa 1951, location undefined | Photo courtesy National Archives, St. George News

That evening, the 213th found themselves advancing into positions with the Chinese in front of them, behind them, and suddenly to the right of them. It was only from the east that retreating Chinese soldiers ran headlong into the U.S. troops.

The fighting was intense, yet surprisingly many personnel at the headquarters’ bivouac, only a couple hundred yards away, remained unaware of the chaos unfolding around them. In fact, some even slept through the entire ordeal, completely oblivious to the danger and uncertainty that gripped the battlefield that day.

“It was really such a focused attack, hitting the far-right side of A Battery and a couple of machine gun positions,” Billingsley said. “They knew the Chinese were out there searching to get back to their lines, but nobody was really sure where anybody was.”

The next day, as the sun came up, A Battery commander, Capt. Ray Cox, led an M7 tracked artillery vehicle up the canyon with approximately 20 American artillerymen comprised of men from both A and Headquarters’ batteries.

“Capt. Cox pulled one of our howitzers off of the firing line and took its .50-caliber machine gun to start strafing the hillside,” said 92-year-old George Matheson of headquarters’ battery. “That gun was so powerful that it chewed up anything it met. We must have killed a lot of enemy troops with that .50-cal. It was then the Chinese started surrendering. I think we ended up capturing 831 prisoners that day.”

For his actions at the Battle of Kapyong, Cox was awarded the U.S. Army’s third highest award for valor, the Silver Star.

In the heat of battle, survival hangs precariously in the balance. Remaining alive is often a matter of luck, timing and an innate ability to make effective decisions in high-pressure situations.

While some men crumble, their bravado evaporating like the morning mist, others fight on, fueled by rage, sheer stubbornness or a commitment to duty, honor, country. Every individual soldier understands unequivocally that war does not embody glory – but instead, represents survival, sacrifice and the never-ending pain of memories that cannot be wiped away.

For Matheson, the passage of time has not dimmed the vivid memories of his Korean War experience. Even after more than 70 years, the challenges of combat remain etched in his mind with remarkable clarity. In an instant, Matheson is transported back to the most pivotal moment of his life — the Battle of Kapyong.

All too easily, the memories come flooding back, as if no time has passed at all.

“The battery was near a small valley that came out of the mountains. We had six howitzers sitting out there on the edge of the valley looking north. We were there waiting and biding our time to see what was going to happen,” Matheson said.

Under normal battle conditions, artillery units are tasked with firing their cannon at distant enemy targets. Yet, the Cedar City and Richfield units found themselves without this advantage, directly confronting the enemy in a battle that lasted approximately 12 hours.

Matheson, not yet 20-years-old, served as a mess sergeant in A Battery, 213th Armored Field Artillery Battalion during the Battle of Kapyong. Initially unaware of the seriousness of the battle, Matheson later learned the tremendous odds the 213th faced.

Brig. Gen. Frank Dalley, commanding general of XI Corps Artillery of the Utah National Guard and former commanding officer of the 213th Armored Field Artillery Battalion in Korea, inspects a battery of M107 (175mm) self-propelled howitzers. In the Battle of Kapyong (also spelled Gapyeong) in April 1951, Allied forces from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States slowed down the Chinese advance. The 213th played a supporting role in this battle, its first combat action in Korea. Date and location undefined | Photo courtesy U.S. National Archives, St. George News

Brig. Gen. Frank Dalley, commanding general of XI Corps Artillery of the Utah National Guard and former commanding officer of the 213th Armored Field Artillery Battalion in Korea, inspects a battery of M107 (175mm) self-propelled howitzers. In the Battle of Kapyong (also spelled Gapyeong) in April 1951, Allied forces from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States slowed down the Chinese advance. The 213th played a supporting role in this battle, its first combat action in Korea. Date and location undefined | Photo courtesy U.S. National Archives, St. George News

“In the middle of the (first) night I had to get up and go to the bathroom,” Matheson said. “I came back and got into my cot and about that time a bullet went over my head and into the wooden (tent supports) above me. I looked up to see this hole right there, so I thought it was about time I slept on the ground. There was a great deal of small arms fire being exchanged. It was terrifying.”

Although Matheson’s position received constant fire from the enemy, he did not feel the Chinese would breach their redoubt, “There were too many guards for them to even try,” he added.

“The next morning, I got up and tried to get into the mess truck to prepare breakfast for the battery,” Matheson said. “But every time I started to climb up into the truck bullets would start whistling past. I guess the troops would have to wait a little while longer to get fed that morning.”

While the battle raged, the U.S. line held.

“We held that line right there, suffering only two people who were wounded in our unit, but we never lost a man,” Matheson said. “Lt. Col. (Frank) Dalley took 600 over there and he brought 600 back alive. He was a good leader … and really cared about his men.”

In a remarkable display of courage and determination, the U.N. forces defied overwhelming odds to emerge victorious at Kapyong, despite being outnumbered by a staggering 7-to-1 ratio with some estimates as high as 16-to-1.

When the battle at Kapyong was over, the U.N. troops suffered 59 fatalities and more than 111 wounded, while Chinese losses were substantially higher, with estimates ranging from 1,000 to 5,000 killed and many more wounded.

The Battle of Kapyong stands as a testament to the bravery and sacrifice of the U.N. forces, who against all odds, secured a crucial victory against a formidable foe. For its actions in battle, the 213th was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for obliterating a Chinese Division.

Mess Sgt. George Matheson, soon after graduation from high school, was activated in 1950. Matheson went on to serve as a mess sergeant with the 213th at the Battle of Kapyong. Date and location undefined | Photo courtesy George Matheson, St. George News

Mess Sgt. George Matheson, soon after graduation from high school, was activated in 1950. Matheson went on to serve as a mess sergeant with the 213th at the Battle of Kapyong. Date and location undefined | Photo courtesy George Matheson, St. George News

While the Battle of Kapyong was undoubtedly a fiercely contested and significant win, certain inaccuracies have crept into the historical record over time, obscuring the true events that transpired, Billingsley said.

“Part of the myth of the 213th is that they were by themselves to fight off 4,000 Chinese. This is not true, but the reality is still a great story,” he said. “You have to think about it. The reason they were in the canyon in the first place was to support the infantry that was all around them.”

Another prevailing myth is that the battle devolved into hand-to-hand fighting.

Contrary to the military’s “official” narrative, the truth, as revealed by multiple first-hand accounts from soldiers who fought at Kapyong, indicate that “The closest the Chinese troops came to the 213th positions were within about 50-yards, maybe as close as 20-yards – pretty close but not hand-to-hand fighting,” Billingsley said.

The final bit of folklore that has seeped into the narrative is that 600 soldiers from Utah deployed to Korea, but the reality is something different, Billingsley added.

The 213th is often associated with Utah, but it was significantly under strength when activated, comprising approximately 300-350 soldiers from the Beehive State, including the command staff and Dalley. To reach its full capacity of about 600 men, the unit was augmented with additional soldiers from across the country.

When asked about his time in Korea, Matheson thought for a minute.

“I had put myself in a position, where there wasn’t any getting out of it, so I figured if I had to serve, I would serve,” Matheson said. “When I came home, they let me off the bus in Richfield. I had my duffle bag and walked a half mile to get home. When I got there my little brother was in my bed. I booted him out and went to sleep.”

Following the war, Matheson went back to the work in his hometown restaurant, attended college at Brigham Young Academy in Cedar City, transferred to Utah State where he graduated in 1956, with a degree in electrical engineering.

“So, I made it, I fulfilled my dream of doing something in electronics after all,” Matheson said, with a grin stretching from ear-to-ear.

This is the second of a three-part series on the Utah National Guard. To read the first story in the series, click here. For the final part of the history of the 2nd Battalion 222nd Field Artillery, continue reading: “From Saigon to Baghdad: The Utah National Guard’s heroic missions Part 3,” on Aug. 18.

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2024, all rights reserved.

David Louis is a native of…well, everywhere. It’s hard to nail down a hometown for David, because when he was growing up, his father wanted to move somewhere else every two or three years. Since 1986, his primary residence has been Las Vegas, where he graduated from the University of Nevada. David has been a journalist collectively for more than 10 years, but as a jack-of-all-trades, he has also been a restaurant manager, warehouse foreman for a piping company, K-8 teacher and limousine driver. Along with a past life as a musician, David enjoys traveling on Amtrak – it’s all about the journey and not about the destination – cooking and painting. His greatest joys in life are his family, too numerous to list, and his cat Maxine.

Source link : http://www.bing.com/news/apiclick.aspx?ref=FexRss&aid=&tid=66b944af7a0c4d09b8590d1efde6c5a1&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.stgeorgeutah.com%2Fnews%2Farchive%2F2024%2F08%2F11%2Fdld-courage-under-fire-the-utah-national-guards-korean-war-legacy-part-2%2F&c=17942517568693578270&mkt=en-us

Author :

Publish date : 2024-08-11 10:29:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.